How Not to Teach Digital Humanities

The following is a talk I’ve revised over the past few years. It began with a post on “curricular incursion”, the ideas of which developed through a talk at DH2013 and two invited talks, one at the University of Michigan’s Institute for the Humanities in March 2014 and another at the Freedman Center for Digital Scholarship’s “Pedagogy and Practices” Colloquium at Case Western Reserve University in November 2014. I’ve embedded a video from the latter presentation at the bottom of the article. There is a more polished version of the article available in Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016.

“À l’ École,” Villemard (1910)

“À l’ École,” Villemard (1910)

In late summer of 2010, I arrived on the campus of St. Norbert College in De Pere, Wisconsin. I was a newly-minted assistant professor, brimming with optimism, and the field with which I increasingly identified my work—this “digital humanities”—had just been declared “the first ‘next big thing’ in a long time” by William Pannapacker in his Chronicle of Higher Education column. “We are now realizing,” Pannapacker had written of the professors gathered at the Modern Language Association’s annual convention, “that resistance is futile.” So of course I immediately proposed a new “Introduction to Digital Humanities” course for upper-level undergraduates at St. Norbert. My syllabus was, perhaps, hastily constructed—patched together from “Intro to DH” syllabi in a Zotero group—but surely it would pass muster. They had hired me, after all; surely they were keen to see digital humanities in the curriculum. In any case, how could the curricular committee reject “the next big thing?” particularly when resistance was futile?

But reject it they did. They wrote back with concerns about the “student constituency” for the course, its overall theme, my expected learning outcomes, the projected enrollment, the course texts, and the balance between theoretical and practical instruction in the day-to-day operations of the class.

- What would be the student constituency for this course? It looks like it will be somewhat specialized and the several topics seems to suggest graduate student level work. Perhaps you could spell out the learning objectives and say more about the targeted students. There is a concern about the course having sufficient enrollment.

- The course itself could be fleshed out more. Is there an implied overall theme relating to digital technology other than "the impact of technology on humanities research and pedagogy"? Are there other texts and readings other than "A Companion to Digital Studies"? How much of the course will be "learning about" as distinct from "learning how to”?

My initial reaction was umbrage; I was certain my colleagues’ technological reticence was clouding their judgement. But upon further reflection—which came through developing, revising, and re-revising this course from their feedback, and learning from students who have taken each version of the course—I believe they were almost entirely right to reject that first proposal.

As a result of these experiences, I’ve been thinking more and more about the problem of “digital humanities qua digital humanities,” particularly amidst the accelerated growth of undergraduate classes that explicitly engage with digital humanities methods. In the first part of this talk, I want to outline three challenges I see hampering truly innovative digital pedagogy in humanities classrooms. To do so, I will draw on my experiences at two very different campuses—the first a small, relatively isolated liberal arts college and the second a medium-sized research university—as well as those of colleagues in a variety of institutions around the country.

As an opening gambit, I want to suggest that undergraduate students do not care about digital humanities. I want to suggest further that their disinterest is right and even salutary, because what I really mean is that undergrads do not care about DH qua DH. In addition, I don’t think most graduate students in literature, history, or other humanities fields come to graduate school primarily invested in becoming “digital humanists,” though there are of course exceptions.

Indeed, we’re now well into a backlash against DH, particularly among many graduate students who feel the priorities, required skills, and reward structures of their disciplines have shifted under their feet in ways they cannot account or adjust for. While I will argue here that the perception of wholesale DH transformation is largely wrong, I would also contend that graduate students’ skepticism of the rhetoric around DH is neither entirely misguided nor inconsequential to those of us who believe DH pedagogy matters to the futures of our fields. Very broadly, then, I will argue that we must work to to take both undergraduate disinterest and graduate resistance as instructive for the future of DH in the classroom. Here are the major challenges I would identify for effective integration of DH into curricula.

1. “What Is DH?” Always Excludes

Let us begin, then, with rhetoric—specifically, the rhetoric with which we often frame the DH field. The rejected course I proposed at St. Norbert revolved around DH itself, and it began with a bevy of articles grappling with the question “What is digital humanities?” “What is DH?” has become a prolific genre in its own right; there are no shortage of such pieces making all sorts of claims about what the field is or should be (If you want a primer, the Digital Humanities Department at University College London has published a book, Defining Digital Humanities, and their director Melissa Terras maintains a regularly-updated bibliography of the genre). What better way to outline the field we would study in this new class, I reasoned, than with such definitional pieces?

Except that it’s not. “What is DH?”—or “Who’s in/out of DH?” or another variation thereupon—are very “inside baseball” genres, by which I mean they are meta-academic genres. “Digital” humanities is often defined in these pieces by contrast to “traditional” humanities. DH is collaborative rather than solitary, DH is interdisciplinary, DH is interested in new scales of analysis, etc. etc. etc. This is because DH practitioners understand from hard-won experience how entrenched fields such as history and literature can be, how suspicious of computationally-informed methods and tools. If you review the DH literature from just before the field’s “next big thing” apotheosis, you will find a deep undercurrent of anxiety: will our work ever be understood, valued, or recognized by our disciplinary colleagues? Our undergraduates, however, are blissfully unaware of the disciplinary reticences that underlie that term, digital humanities, and are not eager for academic courses in which the primary conversation is about the mechanics and politics of the academy itself.

“What is DH?” pieces can be valuable to folks invested in conversations about the humanities, about the future of the academy, and so forth. They help articulate the value of digital scholarship to colleagues unaware or unsure about the work we do. But even here these pieces inevitably fall short. They speak of “DH” as an identifiable and singular thing, even if that thing contains multitudes, when in fact DH is often local and peculiar: a specific configuration of those multitudes that makes sense for a given institution, given its faculty, staff, and students, and given its unique mission and areas of strength.

In one oft-cited “What is DH?” piece (which appeared in the first Debates in the Digital Humanities volume), Matthew Kirschenbaum calls digital humanities a “tactical term” that can help practitioners position themselves for institutional authorization of various sorts:

On the one hand, then, digital humanities is a term possessed of enough currency and escape velocity to penetrate layers of administrative strata to get funds allocated, initiatives under way, and plans set in motion. On the other hand, it is a populist term, self-identified and self-perpetuating through the algorithmic structures of contemporary social media [...] Digital humanities, which began as a term of consensus among a relatively small group of researchers, is now backed on a growing number of campuses by a level of funding, infrastructure, and administrative commitments that would have been unthinkable even a decade ago. Even more recently, I would argue, the network effects of blogs and Twitter at a moment when the academy itself is facing massive and often wrenching changes linked both to new technologies and the changing political and economic landscape has led to the construction of “digital humanities” as a free-floating signifier, one that increasingly serves to focus the anxiety and even outrage of individual scholars over their own lack of agency amid the turmoil in their institutions and profession. Matthew Kirschenbaum, “What Is Digital Humanities and What’s It Doing in English Departments?” (417)

For Kirschenbaum, the “‘tactical’ coinage” of “digital humanities” can be “unabashedly deployed to get things done” (415). As true as this can be, particularly at the administrative level, DH remains a murky term for our colleagues, our students, and, if we were being honest, for those administrators. What’s more, the many options offered in “What is DH?” pieces rarely clarify the question. In my experience, these definitional articles do little to clarify the field for newcomers, except to erect ideas of barriers more rigid in prose than in practice. Indeed, I have never known a colleague read such a piece and come away realizing, “I am a digital humanist after all!”

Even more problematically, for our undergraduate students such pieces simply fall flat. Shockingly, the language of “disciplinary landscapes” and “infrastructure” and “free-floating signifiers” does not set the average undergraduate’s pulse a-twittering. Indeed, to assign such a piece to a class of undergraduates is to forget our audience entirely. Our students are just learning the rules of the humanities game. As Adeline Koh commented on the original version of this post, “to introduce DH discussions on the level that we’re used to may alienate undergraduates, who are only starting to learn the conventions of disciplines that a lot of DH debates are critiquing at meta-levels.”

In the first version of this piece, I posited that using the term “digital humanities” is often a tactical error, particularly when trying to introduce digital humanities into the undergraduate curriculum. In this version of the piece, however, I want to take this point one step further and suggest that our concern with defining and propagating the field writ large can interfere with innovative but necessarily local thinking about digital skills, curriculum, and research at both the undergraduate and graduate level.

In the fall of 2014 I structured even my graduate DH course to avoid the “What Is DH?” genre entirely, and I think the course was better for that decision. Rather than beginning with interminable discussions of what counts or doesn’t, or who’s in or who’s out, we worked toward an understanding of the field’s contours by studying the theories and methods that undergird it, focusing on its projects and critical publications rather than its attempts at self-definition. This still isn’t a perfect model. For instance, I have realized from students’ evaluations that in future iterations we need to spend more time analyzing “case study” projects in depth. But I’ve found “Texts, Maps, Networks” a more productive and stimulating class than its immediate predecessor, “Doing Digital Humanities.”

2. “Humanities” is a Vague and Often Local Configuration

Indeed, you may notice that a course once called “Doing Digital Humanities” has become, in its subtitle, “Digital Methods for Literary Study.” This isn’t because the course is no longer a DH course, or no longer interdisciplinary. In fact, more history students took “Texts, Maps, Networks” than did previous iterations. But I have realized that while my teaching and scholarship benefits enormously from interdisciplinarity, that interdisciplinarity is grounded in my training in textual studies, the history of the book, and critical editing. In my teaching and my scholarship, I have become increasingly convinced that DH will only be a revolutionary interdisciplinary movement if its various practitioners bring to it the methods of distinct disciplines and take insights from it back to those disciplines.

We shouldn’t forget, of course, that “humanities” is not itself a self-evident signifier. What “humanities” does and does not comprise differs from definition to definition and from institution to institution. For our students, as for many of us, the word humanities is opaque, vaguely signaling fields that are not the sciences. Even that broad definition is hazy. Consider anthropology, which is in some institutional structures a humanities field and in others a social science; the same sometimes goes for history. To talk about “digital humanities,” then, is not to talk to our students, but to talk to each other. I write this not to disavow that important conversation, but to suggest that it needn’t interfere with our teaching.

Stop calling it "digital humanities." Or worse, "DH," with a knowing air. The backlash against the field has already arrived. The DH'ers have always known that their work is interdisciplinary (or metadisciplinary), but many academics who are not humanists think they're excluded from it. As an umbrella term for many kinds of technologically enhanced scholarly work, DH has built up a lot of brand visibility, especially at research universities. But in the context in which I work, it seems more inclusive to call it digital liberal arts (DLA) with the assumption that we'll lose the "digital" within a few years, once practices that seem innovative today become the ordinary methods of scholarship.William Pannapacker, “Stop Calling It ‘Digital Humanities’”

Attempts have been made to revise the terms we use. Bill Pannapacker recently proposed “Digital Liberal Arts” as a replacement for DH, particularly at small liberal arts colleges in which a wider range of fields might be wanted to rally under the banner. And it seems that DLA has gotten some traction at several institutions. But for undergraduates, I would argue “digital liberal arts” misses the mark just as badly as “digital humanities.” For many undergraduate students, “liberal arts” signifies no more than “humanities,” and I actually suspect “digital” signifies in ways quite opposite to our intentions.

3. Undergraduates are Scarred by Digitality

We pair “digital” with “humanities” and feel we have something revolutionary, but for our undergraduate students the word digital is profoundly unimpressive. Their music is digital. Their television is digital. Many of their books and school materials are and have always been digital. To brag that our humanities (or our liberal arts) are digital is to proclaim that we’ve met a base requirement for modern communication. It would be like your bank crowing that you can check your account online. Of course you can. At this point, you would only notice if you couldn’t.

Far from signaling our cutting-edge research and teaching, I suspect that the phrase “digital humanities” often raises perfectly valid worries with our students, many of whom have spent their entire educational careers sleepwalking through ed tech nightmares. The point I want to make here is exactly opposite familiar refrains about “digital natives.” That our students have spent their educational lives using digital tools—researching online, using applications to learn math or spelling, listening to Powerpoint lectures and then downloading the slides, or even drawing boxes around the Mona Lisa’s face on a Smartboard—does not mean that they’ve learned all that much about or from those digital tools.

These same students then came to universities being “disrupted” by the MOOC evangelists, though these students’ very presence in our universities perhaps signals that they realized before many faculty and administrators that self-guided higher education from recorded lectures is not the newest thing in the world. Of course, MOOCs are hardly synonymous with digital humanities, and indeed, DH practitioners have been among the most critical of the MOOC movement, which largely transplants a lecture-based model of education online. But our students’ perceptions of educational technology are bound to shade their reading of tech in humanities classrooms.

In short, I worry that we dismiss our students’ reservations about DH too blithely. Our students’ technological skepticism—which is often expressed through the language of “I’m not very good at computer stuff”—is not the same as our colleagues’ technological skepticism. Many of our students honestly, truly, really choose literature or history or art history or religious studies because they wanted to read and think deeply rather than follow what they perceive as a more instrumentalist education in business or technical fields. To do so they often resist substantial pressure from family and friends pushing them toward “more practical” majors, which are often (though incorrectly) perceived to be more technical majors. Of course, DH can help students read and think deeply, but we would do well to try and see this exchange from our students’ perspective.

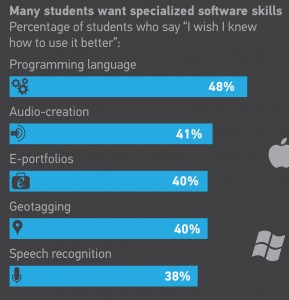

“From and ECAR National Study (2011)

“From and ECAR National Study (2011)

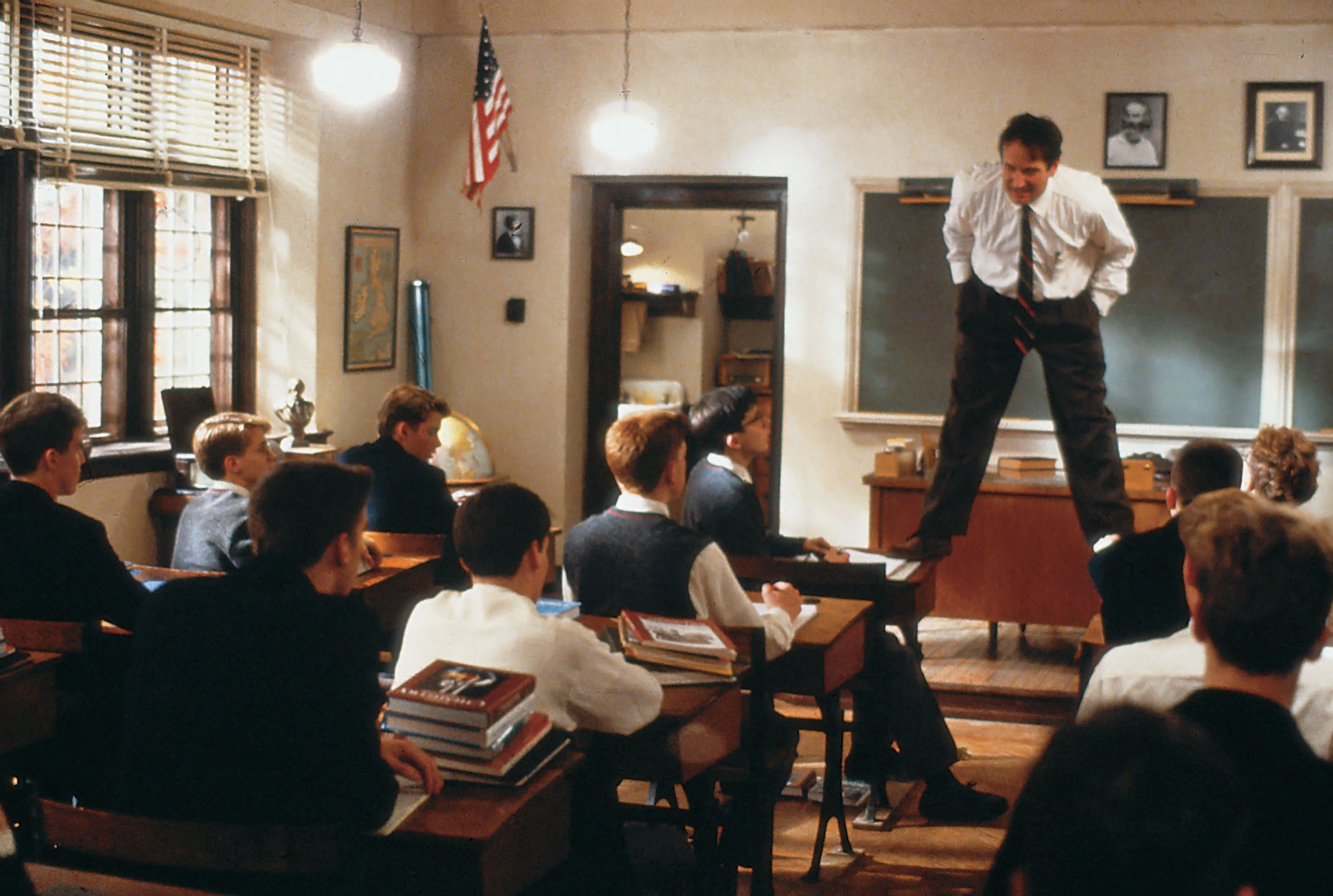

In many ways, I think the way we often frame DH tries a bit to hard to achieve a Dead Poets Society moment: “your other teachers taught you literature with close reading and literary criticism, but in my class we’re going to disrupt that stale paradigm using computers. Now rip up your books and pull out your laptop!” But those attempts fall flat, for all the reasons I’ve tried to articulate above. Indeed, a growing body of evidence from students seem to correlate at least two of the points I’ve made here. A 2011 survey by EDUCAUSE, for instance, found that only 1-4 students believe strongly that “their institution uses the technology it has effectively.” The survey tells us also a good deal about what students (or perhaps more to the point, what EDUCAUSE) believes “technology” entails—namely, hardware and commercial software. Few students surveyed believe their instructors use technology effectively, and a majority believe they understand technology better than their teachers. For such a student, imagine how it must sound to hear her teacher talking up “computers” and “digital tools.”

Robin Williams in Dead Poets Society

But DON’T PANIC.

Because students do love doing DH things, when those DH things are framed around particular skills and often within disciplinary structures. And I would argue more and more that the way we should integrate DH into the undergraduate curriculum is as a naturalized part of what literary scholars or historians or other humanists do. Teach distant reading alongside close reading and don’t worry about proving how revolutionary the former is. Such an approach also lowers the barrier for “doing dh” in the undergraduate classroom. You don’t have to be a DH expert to create—or better yet steal—a few exciting DH assignments.

“From and ECAR National Study (2011)

“From and ECAR National Study (2011)

I find it helpful to look back at that EDUCAUSE report and infographic again, this time focused on what students reported wanting to learn more about. When asked what skills they wished they knew better, students responded programming language (48%), audio creation (41%), e-portfolios (40%), geotagging (40%), and speech recognition (38%). These skills have little to do with particular hardware or commercial software. Indeed, the skills students want are those which would allow them to create their own digital work, and perhaps even their own tools—in other words, they want to learn to engage with, and not simply use, technology in the classroom.

So how do we do this in the humanities? In the remainder of this post I want to offer four principles for curricular incursion that have worked well in my own classes at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. I will use examples from a few of my courses, but I will draw most heavily on “Technologies of Text,” the course I revised based on the curricular committee rejection with which I started this piece. Where “Introduction to Digital Humanities” failed, “Technologies of Text” succeeded, and I think after teaching it (and thus revising it) four times I’m beginning to understand why.

1. Start Small

My first principle is simply to start small. You do not need an entire DH curriculum, or even a designated DH course, to introduce substantial digital pedagogy into your classes. In departments with a single faculty member interested in digital humanities—and this describes a significant proportion of humanities departments—small beginnings help instructors focus on what DH they can teach effectively. To be frank, I was not prepared to teach all of the DH in that “Intro to Digital Humanities” course I proposed. By contrast, my “Technologies of Text” class is in essence a book history class with a strong DH undercurrent. Maintaining such disciplinary focus perhaps limits my students’ sense of the wider DH field, but it allows me to teach a few things well rather than teaching everything poorly. And indeed, my graduate course has moved in the same direction. Over the years my syllabus has shifted from a rapid introduction to as many methods and tools as possible to a more focused introduction to a few tools, methods, and theoretical conversations I know very well. In the older version of my graduate course, in which I did try to survey all of the DH, I felt students left with only a glancing understanding of any aspect of the field. In the current version, students leave with fewer but more well-developed skills from which they can build.

My courses aptly illustrate the challenges that Rafael Alvarado suggests the larger field faces in defining itself. Alvarado claims that “there is simply no way to describe the digital humanities as anything like a discipline” in large part because of the sheer amount of skill and knowledge such a claim would require of DH scholars and teachers. If coverage is the aim of our “Introduction to DH” courses, only such polymaths could effectively teach those courses.

[T]here is simply no way to describe the digital humanities as anything like a discipline. Just think of the curricular requirements of such a field! Not only would the field require its members to develop the deep domain knowledge of the traditional humanist—distant reading notwithstanding—it would also demand that they learn a wide range of divergent technologies (including programming languages) as well as the critical discourses to situate these technologies as texts, cultural artifacts participating in the reproduction of social and cognitive structures. Granted the occasional polymath who may master all three, the scope of such a program is simply too vast and variegated.Rafael Alvarado, “The Digital Humanities Situation”

In many of my courses, one way students start small with DH skills is through closer considerations of digital media for scholarly and popular communication. One of my students, for instance, used a Tumblr to analyze fandom communities on Tumblr. By working in the platform she was analyzing, she was able to directly interact with the communities under study, which enriched her argument significantly. In a course most broadly about book history, students can directly contrast the affordances and limitations of digital and print technologies, as in this student’s remediation of Montaigne’s essays into blog form (and be sure to read the FAQ). Neither of these examples required extensive technical expertise from students or instructor, but such projects cultivate media thinking that could inform a deeper engagement with DH methods later in this class or in another. Indeed, as the video below demonstrates (if you can excuse the elevator music behind it), the Tumblr project discussed here did blossom into a wider interest in digital humanities for the student who produced it, and expanded it as part of her thesis.

2. Integrate When Possible

My second principle builds on the first: integrate when possible. “Technologies of Text” teaches many DH ideas and skills: in our labs we edit wikipedia, encode documents in TEI, learn the basics of computational text analysis, or program chatbots using the Python programming language.

Students in my Technologies of Text class transcribe by candlelight.

These labs, however, are framed not within a narrative of recent scholarly revolution, but instead within a sweeping discussion of book and media history. Before students learn to operate a 3D printer, then, they have transcribed manuscripts by candlelight in a simulation of the medieval scriptorium, made rag paper, set type and printed on a letterpress, visited the National Braille Press, and spent significant time in the Rare Books room at the Boston Public Library. Each of these labs helps students understand technology not as something we invented ten years ago (give or take), but as a long continuum of human activity.

Our primary objective in this course will be to develop ideas about the ways that such innovations shape our understanding of texts (both classic and contemporary) and the human beings that write, read, and interpret them. We will compare our historical moment with previous periods of textual and technological upheaval. Many debates that seem unique to the twenty-first century—over privacy, intellectual property, information overload, and textual authority—are but new iterations of familiar battles in the histories of technology, new media, and literature. Through the semester we will get hands-on experience with textual technologies new and old through labs in paper making, letterpress printing, data analysis, and 3D printing. The class will also include field trips to museums, libraries, and archives in the Boston area.“Technologies of Text” course description

By the end of this course, you will:

- Understand technology and new media as historical rather than exclusively recent phenomenon;

- Analyze books and other textual technologies as material objects and within their social contexts;

- Experiment with a range of textual technologies, both historical and modern;

- Examine interplays, both thematic and material, between literary works and contemporaneous technological innovations;

- Draw parallels between literary studies and diverse fields such as information science, computer science, communications, and media studies;

- and Create original, public, creative research projects using archival materials

“Technologies of Text” course objectives

By contextualizing our moment of digital remediation historically, as but the latest phase in a long history of textual reinvention, I help students understand why my assignments ask them to experiment across modalities. Those assignments push them beyond their comfort zone—for English students, their comfort zone is writing a 7 page paper—asking them to consider the medium as well as the message of their own research and arguments.

Technologies of Text students set type and print at the Museum of Printing in North Andover, MA.

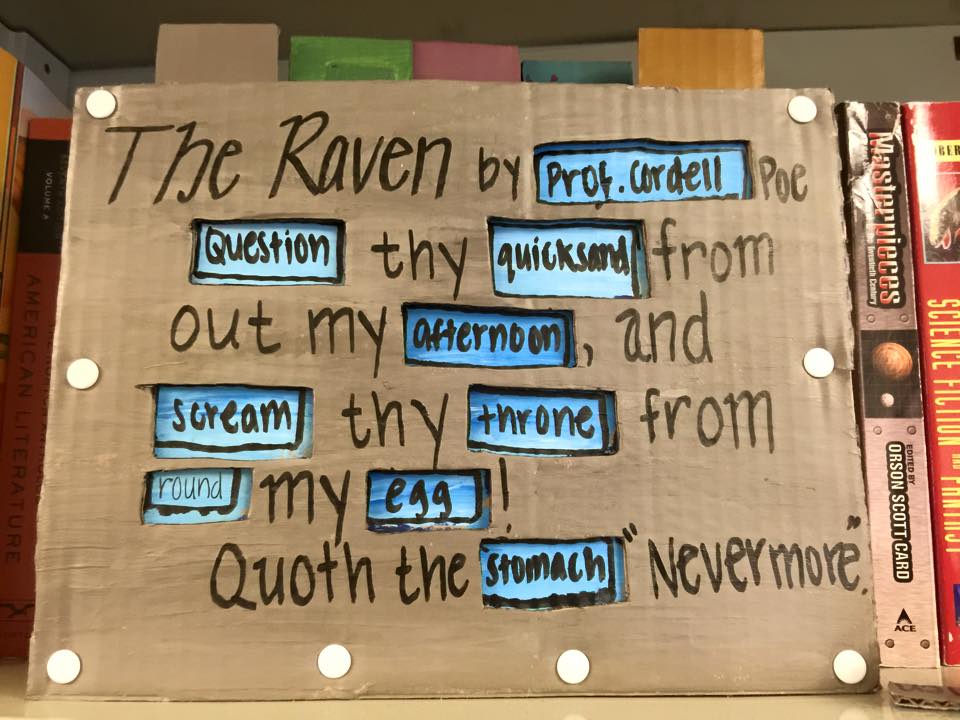

These labs prepare students to develop their own “unessays” as midterm and final assignments. I am hoping to develop another post about these unessays, and so won’t belabor a discussion of them here, but I do want to highlight the broad range of engagements students choose in the model unessays linked from the assignment, which include theoretical engagements with media, personal TEI encoding projects, video essays, argumentative listicles, altered books, built morse code devices, and even physical “twitter poetry bot” generators.

Part of a “Technology of Text” student’s unessay, in which she created a physical “twitter poetry bot” along the model of those we’d built in Python for one of the course labs.

These disparate assignments allowed students to grapple with those aspects of the course they found most compelling, both in terms of content and in terms of technology and method. In an “Introduction to DH” course these engagements might not all make sense, but under the rubric of book and communications history they certainly do. For several of these students, working on such assignments did generate a broader DH interest, and they have developed personal DH projects or gone on to work for other DH projects ongoing at Northeastern.

3. Scaffold Everything

In order to move our students toward this kind of engagement, however, we must scaffold everything, from the introduction of new skills into particular classes to the progression of skills through a curriculum. The necessity of such scaffolding brings us back to the mistaken notion of the “digital native”—a notion, I would argue, that leads to frustration for both students and teachers. The idea that our students must have innate technological skills because they’ve grown up in a computer-saturated world is equal, to my mind, with assuming all drivers must be excellent mechanics or auto designers because they’ve spent so much time behind the wheel or, perhaps more germanely, to assuming all students must be innately gifted writers because they’ve grown up around books and paper. We know the latter isn’t true—indeed, the very existence of college writing programs belies the idea—but we somehow persist in the former delusion when the fact is that our students need as much guidance thinking about and working with technologies of all kinds as they do writing a cogent argument. Indeed, these two tasks can be wonderfully coupled, as I hope some of my classroom examples illustrate.

In making these points, I mean not to impugn our students’ abilities. Decades of scholarship in rhetoric and composition have shown two very interesting things: first, at least since the late nineteenth century each generation of college students has been writing at about the same relative ability level as the previous generation, though our demands of college writers have steadily increased over time. And second, at least since the late nineteenth century, each generation of college professors has been certain that “kids today” write far worse than their own generation did. Taking these historical studies as instructive, then, I mean only to suggest that so-called “digital natives” are neither more nor less innately adept at computational work than “digital immigrants.” When introducing digital humanities into our classrooms, we must structure those introductions for students with a wide range of technical backgrounds and aptitudes.

Certainly technological imagination is not now nor has ever been innate. Yes, our students have grown up with apps and iTunes and YouTube—but it is one thing to be able to use a particular piece of hardware or software, and another thing altogether to imagine what it might do or mean if pushed beyond its typical use, or even more again to imagine what might be created in its stead. It’s these latter skills that good digital humanities pedagogy must inculcate: not “how to use x tool,” though that’s likely part of it, but more “understanding how x functions, delineating its affordances and limitations, and then imagining y or z.”

In an interdisciplinary course I taught on “Mapping Boston,” for instance, students used Neatline in their final projects to build “deep maps” of particular neighborhoods or landmarks in the city, layering historical photographs, maps, geospatial data, literary texts, and other elements to build arguments about their city. These final projects grew out of a semester of labs in which students learned to work with geospatial data in GIS, georectify historical maps in Map Warper, and manage digital archival objects in Omeka. I was particularly struck by those students who worked to push Neatline to its limits. Consider this student’s project on the 1919 Molasses Flood in Boston’s North End, or another student’s project on the history of Boston’s Harbor Islands. Both are messy in their way—we did not have time to revise these projects for usability as I would wish—but I impressed by how these projects in particular integrated so many of our course methods and theoretical conversations, and the creativity with which they approached the idea of “mapping” as interpretation. Both of these students brought to our seminar interests from their majors and previous courses, and both continued to think about mapping in subsequent classes in their majors.

4. Think Locally

In order to scaffold across classes, of course, we must have a clear sense of where DH skills and courses fit into our institutions. We must think locally, and create versions of DH that make sense not at some ideal, universal level, but at specific schools, in specific curricula, and with specific institutional partners. One major objection to my rejected “Introduction to Digital Humanities” was that I wanted to offer it at the junior or senior level. Introductory courses, the curricular committee noted, are offered at the 100 level. Courses at the 300 and 400 level should build on those introductory courses.

I was at first perturbed by what I saw as semantic pedantry, but as a new professor I had little sense of how such committees operate, and how they work to structure students’ experiences through their time at a given institution. Since then I’ve worked on such committees and largely come to understand their perspective. I was tacitly assuming that my course would build on skills that students picked up in their lower-division courses. I expected my students to be competent researchers and independent workers. I planned to build on their work in lower-division literature and history courses. I was in essence proposing a digital capstone to the traditional humanities skills they’d picked up elsewhere in the curriculum, and my colleagues were right to worry that branding it an “intro” would confuse students and advisors about the aims and activities of the course.

This is a very specific example, but there are broader implications. Thinking locally can help you connect DH classes and projects to collections, colleagues, and your institution’s mission, all things more likely to generate student enthusiasm and buy-in, and perhaps also cooperation from colleagues and administrators. By thinking locally you can link your courses to libraries, museums, research centers, or other campus-level initiatives. Students love to build projects that make use of their institution’s collections and contribute to their institutions’ legacy, and these often public projects can energize them to work that much harder, as they can create materials with a chance of life beyond the classroom itself. As a bonus, such projects give faculty the chance to work closely with librarians and other colleagues we might otherwise see only for short information sessions.

When I taught at St. Norbert College, for instance, our collections were very specialized, relating primarily to the holdings or records of the Norbertine Order that founded and supported the college. For their class projects, then, my “Technologies of Text” students worked with the materials we had, primarily through the Center for Norbertine Studies. One team created an exhibit of Canon Missae in the Center’s collections, for instance, while a biology student delved into the papers of a prominent Norbertine biologist who had worked at the College. Working with these materials benefited the students, who felt they were contributing to their institution, and the college as well, giving a public face to its hidden collections.

Whither "Digital Humanities"?

[I today learned that Lee Skallerup Bessette recently gave a talk titled “Wither DH?” Clearly she beat me to the pun!]

All of these reflections bring me—as always, it seems—to the term digital humanities itself. I wrote in the earlier version of this piece that “digital humanities will only remain a vital interdisciplinary movement” if it speaks self-consciously back to the legacy fields to which its practitioners also belong. In Digital_Humanities, the authors argue that humanities disciplines need to each establish agendas for computational practices—not as a way to assimilate, per say, but instead as a way to generate vital, critical, experimental questions that will keep the field moving forward.

Maintaining criticality and experimentation means challenging received tradi- tions, even—perhaps, especially—those that defined the first generations of Digital Humanities work. Innovative forms of public engagement, new publishing models, imaginative ways of structuring humanistic work, and new units of argument will come to take their place beside the pioneering projects of the first generation.This means embracing new skill-sets that are not necessarily associated with traditional humanistic training: design, programming, statistical analysis, data visualization, and data-mining. And this means developing new humanities-specific ways of model- ing knowledge and interpretation in the digital domain. It means showing that in- terpretation is rethought through the encounter with computational methods and that computational methods are rethought through the encounter with humanistic modes of knowing. THE HUMANITIES NEED TO ESTABLISH DISCIPLINE-SPECIFIC AGENDAS FOR COMPUTATIONAL PRACTICEAnne Burdick, Johanna Drucker, Peter Lunenfeld, Todd Presner, and Jeffrey Schnapp, Digital_Humanities

But if “digital humanities” is not a meaningful term in undergraduate classrooms, and graduate students and faculty are charged with developing discipline-specific computational approaches, then why use DH at all?

Perhaps “digital humanities” will one day fall away, as some have predicted. If it falls away because DH methodologies have become widely-accepted as possible ways (among many) to study literature, history, and other humanities subjects, this seems to me a fine outcome. But that is not the DH situation right now. Despite the attention the field has received over the past few years, it remains a very small cohort. There has certainly been a slight uptick in DH hiring over the past few years, but as a result we often forget that the vast majority of humanities departments include no digital humanities scholars. Indeed, as Roopika Risam showed in 2013, rumors about the DH job market greatly outpace the actual numbers of DH jobs or hires. We forget also that junior faculty hired to “do DH” for their institution face a steep challenge actually doing that work and making it legible to their colleagues at tenure time. Many colleges eager to “get a DH person”—and as a subtext, often, to begin getting grant money—have not well considered the infrastructure required to do DH well—and, as a corollary, to do DH in a way that will attract grant money. And certainly the vast majority of schools, including those actively working to build DH, have not actively reshaped their tenure and promotion guidelines to reward the kinds of knowledge that DH projects often produce.

In such an environment, digital humanities remains a useful banner for gathering a community of scholars doing weird humanities work with computers. And I suspect it will continue to be useful for awhile yet, long after the current wave of DH mania subsides, I hope, into a more productive rapprochement with the larger humanities fields.