Growing Up Under the “Lost Cause”

In response to white supremacist violence in Charlottesville—the city where I earned my Ph.D. and which I still call home—and another in my current home of Boston, I spent some time on Twitter interrogating my own upbringing in the “Lost Cause of the Confederacy” myth. I wrote far, far more than I anticipated when I began, but the lengthy thread seemed to resonate with folks. I’ve tried to (mostly) gather the thread below, but have used the less constricted blog post medium to expand in a few spots and provide some useful links. This is much more personal than what I usually post on the blog, but it was a moment of introspection directly linked to my current research and, frankly, it felt increasingly necessary to move these thoughts out of the stream and into a more stable medium.

However, the main reason that Confederate monuments need to come down isn’t their effect on white Southerners: it is because of the violence they invoke and perpetuate against Americans of color. If you haven’t already, before reading my post, read (at least) Bree Newsome’s Washington Post OpEd, Jia Tolentino’s piece about Charlottesville in the New Yorker, and the the Southern Poverty Law Center’s report on Confederate monuments.

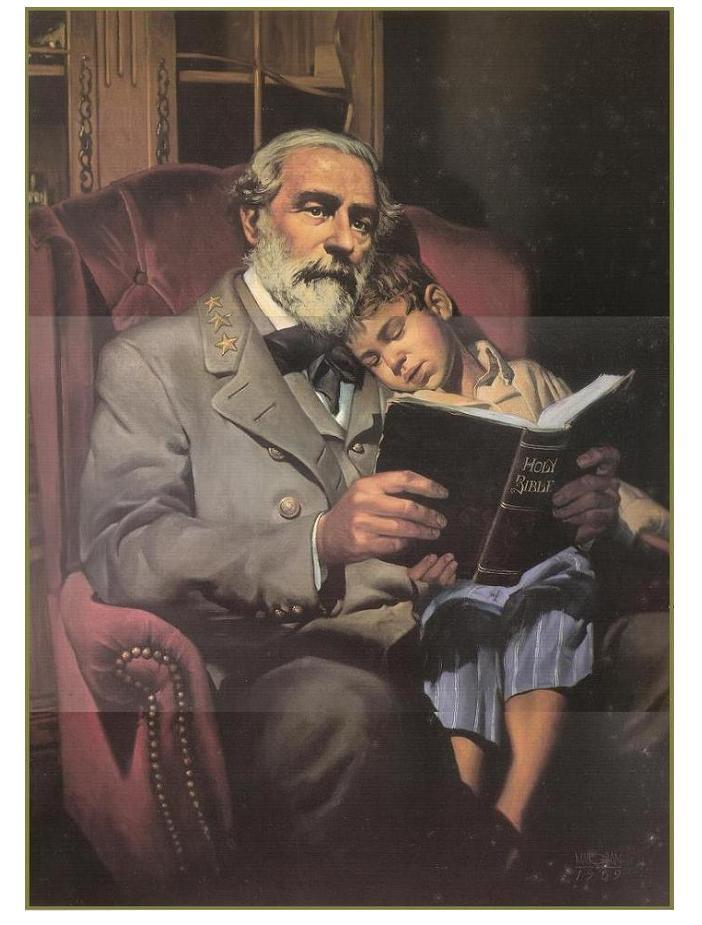

In doing research during the writing of this post I found images of the paintings from my parents’ house. This copy of “The Christian General” was found on a Confederate heritage website I would prefer not to send traffic toward, along with the explanation of the painting lower down in this post.

Look, I understand the Lost Cause myth. It’s pervasive and pernicious. I teach and live now in Boston, but my people are from Georgia. My dad was an officer in the Army for 30 years, including my entire childhood. We moved around a lot, but my cultural background is lower-middle-class white Southern. Most of the Army bases on which we lived were in the South or Midwest: Georgia, Virginia, Tennessee, Kansas, Kentucky. Growing up I was steeped in the myth of the Lost Cause.

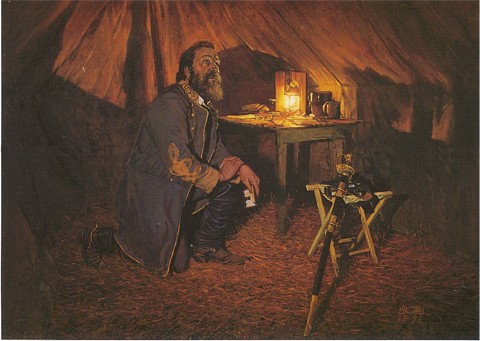

There were precisely two paintings hanging up in my house, which remember was the home of a US Army officer: one of Robert E. Lee and one of Stonewall Jackson. [Later in writing this original Twitter thread I found the paintings themselves online; I include those links earlier here for context] In Jackson’s—titled “The Prayer Warrior”—he was kneeling in prayer in his field tent, holding a bible in his hand and with eyes cast up toward heaven. In “The Christian General” Lee was sitting in an armchair, still in uniform, reading the Bible, with a sleeping child in his lap. Those hagiographic paintings are part of the same tradition as the Confederate statues in Charlottesville, and Durham, and across the US. Their message aligned with the history I was taught indirectly from my family and their friends, as well as directly through textbooks, biographies, and historical fiction. Among many other things, those histories insisted that men like Lee and Jackson didn’t really fight on behalf of slavery, that they were soldiers, Christians, and Virginians first. That they went to war reluctantly, out of patriotism—that their treason was virtue that redeemed any inadvertent support they gave to human bondage. That inadvertent support was wrong, obviously, but only in retrospect. We cannot, the myth insists, judge them by enlightened modern standards, despite the fact that a great many of their contemporaries already recognized chattel slavery as intrinsically evil.

As a kid I bought it. I wrote school book reports on Lee and Jackson. I thought of them in a straight line with Washington. I talked about them as brilliant underdog generals who won against great odds before being overwhelmed by the brute, industrial North. I visited the Atlanta Cyclorama and cursed General Sherman for wantonly pillaging innocent people on his march to the sea.

![This description of "The Christian General," found on the same Confederate heritage site mentioned above, well illustrates the double consciousness I write about in this post. Lee is lionized as "one of the greatest spiritual men of the 19th century...with the conviction of the Holy Spirit," while his army comprises "brave solider[s] in grey, many "thousands" of whom "received Jesus as their personal savior" while serving under Lee. In seven paragraphs about Lee, slavery or indeed secession are not mentioned one time.](/img/121712002.jpg)

This description of “The Christian General,” found on the same Confederate heritage site mentioned above, well illustrates the double consciousness I write about in this post. Lee is lionized as “one of the greatest spiritual men of the 19th century…with the conviction of the Holy Spirit,” while his army comprises “brave solider[s] in grey, many “thousands” of whom “received Jesus as their personal savior” while serving under Lee. In seven paragraphs about Lee, slavery or indeed secession are not mentioned one time.

My history books didn’t counter these messages. My churches didn’t counter these messages. My family didn’t counter these messages. And so I believed them. I should add here that I’m not trying to pin the blame for this miseducation on my parents. My parents’ generation didn’t create the Lost Cause: they were at least the third generation to grow up under the myth. My father would likely say that he never thought anything was strange about the Confederate statues dotting the Georgian landscape where he grew up, and that is precisely the point. The Lost Cause had fully insinuated itself by that time. It is a mark of how insidious the Lost Cause was both in the culture of the South and far beyond that, in a 30 year career as an officer in the US Army, no visitor (to my knowledge) ever commented on the absurdity of two treasonous generals memorialized on the walls of my parents’ home. I’m not writing this to excuse anyone, but only to emphasize that my miseducation perpetuated a multi-generational rewriting of Southern history. My family wasn’t virulent white supremacist household; it was a typical white Southern family, which is my point.

Growing up under those paintings and among those monuments, I understood slavery was wrong—in an abstract way—but I was well trained to disassociate Confederate heroes from slavery. The cause of the war was all states’ rights in the accounts I was given, both at home and at school. This disassociation in turn fostered a double consciousness in which slavery could be “bad” while those fighting to maintain it could be “heroes.” It allowed me to see Confederate monuments everywhere but not reckon their horror. It allowed me to be proud of a “Southern heritage” that did not include the ideas or experiences of the South’s black citizens while feeling modern because slavery was over and racism was “wrong.”

While Confederate generals were disassociated from slavery through an absurd insistence on their own private abolitionism, slavery itself was defanged in nearly every account of it I was given. Looking at my childhood from my current perspective as a scholar of the nineteenth century, I’m struck by how thoroughly my education about slavery mirrored the arguments of slaveholders from the nineteenth century. We were taught that slavery was “wrong” but also that most slaves were treated kindly: “there were some bad apples, sure, but most slaveholders would not have willfully damaged valued assets” We were taught that, “of course, slavery wasn’t ideal, but it brought the Gospel to millions who would otherwise have died in sin in Africa.” We were taught that slavery would have ended of its own accord had the Yankees just kept their jealousy at bay a few more years. There are many, many resources online for debunking these myths, but the actual reasons Southern states gave for seceding are a good place to start (spoiler: they had slaves and wanted to keep them). My childhood education never discussed the many explicitly racist and white supremacist historical documents of the Confederacy, instead claiming extraordinary insight into the private beliefs and feelings of its heroes, which were offered as redemptive of their very public actions.

My Lost Cause education was certainly complicated during my undergraduate program, but I didn’t really start reassociating slavery & Confederacy until graduate school. Suddenly I found myself reading nineteenth-century Southern newspapers that defended slavery in arguments very like those I’d read in the 1980s, though without a veneer of anti-racism. Arguments for white supremacy and racial hierarchy were explicit, rather than implicit, in those historical documents. Reading accounts of enslaved people themselves made clear that the physical and psychological violence of slavery were better documented and widely understood in the mid nineteenth century than in the late twentieth. Slave narratives were another genre quite absent from my childhood education, save vague gestures toward the “heroism” of Harriet Tubman—made all the vaguer because the entire context of her life’s work made no sense against the backdrop of the genteel plantation life we were otherwise sold. Reading nineteenth-century sources, however, it was patently, explicitly, painfully clear Southerners in 1861 went to war to defend slavery, and just that. My childhood history was a myth.

Thinking through my upbringing in the Lost Cause perhaps helps explain how so many white people today can watch white supremacist marches in Charlottesville and beyond, claim a kind of horror about them, but also claim a distance between those marchers and the “real issue” of the statues. We were taught that the KKK and neo-Nazis were relics of history, certainly “bad” also in abstract way, but also that the Lost Cause myth wasn’t really about them. No one peddling the myth in schools or churches would have claimed racism, because the Lost Cause masked white supremacy as virtue, faith, and patriotism. Our current President and the leaders of supremacist groups focus on monuments because they hope to activate this deep, pervasive training in the Lost Cause myth that says racism is “evil” while perpetuating racist norms under the guise of history, or of law and order.

I’m not saying anything new here. Black intellectuals and activists, in particular, have been saying these things clearly and forcefully for as long as the Lost Cause myth has existed, as W.E.B. DuBois illustrates in an essay on Lee’s legacy written in 1928, to cite only one example. My voice is not needed to validate these truths. Instead, I’m trying to grapple with the ways that monuments (and paintings, and books) can obscure these truths to those born into the myth. As a graduate student in literature, I thought of myself as smart, liberal, open minded, but the mythology of Lee and Jackson persisted far too long. Hell, it’s still there. I have to recognize that fact. I don’t flinch enough when I still see the paintings of Lee and Jackson hanging in my parents’ house.

This is the painting of Jackson from my childhood home. Here, too, I prefer not to link to the vendor still selling this painting.

I saw those two paintings every. single. day. They were (nearly) the only two pieces of art in my childhood homes.1 “The Prayer Warrior” and “The Christian General” portrayed Lee and Jackson entirely through their faith and service. The prominence of the Bibles in these paintings aligned with the prominence of the Bible in the evangelical faith tradition central to my family’s religious and social lives. Knowing slavery was “evil” and these men were Christians, I could only imagine these men rejected slavery. How could I not believe the Lost Cause myth? I’m not trying to make excuses. I’m trying to explain how & why I was complicit in the tacit acceptance of this myth for so much of my life.

This is one reason the Confederate monuments must come down. Every year they stand makes the Lost Cause myth easier to sell. Every year they stand the distance between the Civil War and the erection of monuments during the Jim Crow era seems less significant. The statues are bad history, but bad history can calcify. There are too many white people not marching, wondering “what’s the big deal?” is about these statues. I hear it from family on Facebook who insist that they never even noticed those statues while likewise insisting that removing them would do incalculable damage to history. Here again is the double consciousness of those well trained—as I was—to see Confederates as entirely separate from slavery. They believe that the story told by those monuments is history.

My entire adult life I have been unlearning the Lost Cause myth. I still am. Most white southerners are not going to get a Ph.D. to unlearn the myth. Tearing down the monuments will not destroy the myth, either, but it will make it just a little more difficult for the Lost Cause to insinuate itself into the quotidian details of life in the South (and too far beyond).

-

Outside the heat of a Twitter thread, I must acknowledge this isn’t quite true. I can remember one other painting, of a covered bridge, that hung in our homes. It was designed to blend in and in my memory it did just that. The paintings of Lee and Jackson were different because they were sought out, framed elaborately, and hung prominently. Later another painting was added, of a Civil War battle, though I don’t remember which one. I do believe that painting too focused on Confederate troops. ↩