Programmable Type: the Craft of Printing, the Craft of Code

The talk below was developed for lectures during the Congreso Internacional Las Edades del Libro at UNAM in Mexico City and THATCamp Vanderbilt 2017 in Nashville. I’m grateful to participants at both events for their insightful questions and comments, and I welcome feedback from readers on this blog as I further develop this piece.

This is not a talk about coding as it pertains to definitions of the digital humanities, or which seeks to graft some notion of programming to the boundaries of that discipline. To be direct: I don’t think one must code in order to call oneself a digital humanist. And now to be fair: I see little evidence that many scholars in the field equate the field with coding, though that pairing has become a pervasive truism about the digital humanities. I would insist that a single, three-minute position paper cannot serve as metonym for any field, DH included (or even as a metonym for a particular scholar’s full range of views. There are many ways to engage with the digital humanities; coding is one of them.

Rather than making that argument, I want situate the kinds of programming typically practiced in digital humanities research and teaching in relation to practices more familiar to book historians and bibliographers, such as the work of compositors and printers working with moveable type. While not precisely analogous, letterpress printing and programming share essential features of deliberation, planning, execution, industry, and automation that, through specific comparison, can bring qualities of each practice into relief. I want to position both composing and coding as textual craftwork, linked through their formalism: the precise structures of cold type, furniture, and printing frames in one instance and the equally exacting structures of functions, loops, and data frames in the other.

By adopting this frame, I hope to illuminate particular modes of thought and labor that have shaped and continue to shape textual production and transmission. In my work and teaching, I seek to take up N. Katherine Hayle’s insistence that “we can no longer afford to ignore the material basis of literary production…for without it we have little hope of forging a robust and nuanced account of how literature is changing under the impact of information technologies.” Essentially, for Hayes these material bases include the computer. She narrates her own intellectual encounter with “the desktop computer” as she “understood it could be used to create literary texts” and “realized that everything important to her met in the nexus of this material-semiotic object…It confronted her with the materiality of the physical world and its mediation through technological apparatus.”1 A computer is every bit as material an artifact as a printing press , though we often talk of these newly ubiquitous apparatus, to borrow Hayles’ apt word, as if they were objects made of mist rather than metal, plastic, and wire.

I will trace a comparison between printing and programming first from a pedagogical perspective, drawing on my experiences teaching both letterpress printing and programming in an undergraduate course, “Technologies of Text”, to reflect on the ways that pairing these activities help students grapple with the imbrication of reading, writing, publication, and technology across literary history. Second, I will draw on recent experiments from my research with the Viral Texts Project to show how computational text analyses can open recursive exchanges between humanistic data and the historical objects from which they are derived. As I explore each of these perspectives on programmable type, I hope most broadly to illustrate the inextricable relationship between the material and the digital in our technologies of text.

Any comparison drawn between composing and coding will necessarily be metaphorical or analogical. As such, I want to invoke Elyse Graham’s recent piece on “The Printing Press as Metaphor” in Digital Humanities Quarterly, in which she interrogates the technological triumphalism of most “tropes that join Zuckerberg with Gutenberg” and “respond to market imperatives” through a rhetoric, but not a reality, of “revolutionary change.” In particular, Graham argues,

[W]hen we use the printing press as a metaphor for changes in our information culture, we succumb to anachronism twice. First, this metaphorical use relies on a now-belated concept, dating to the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution, of a single artifact that can represent a wider matrix of political, social, cultural, and institutional effects while diffusing specific claims about what those effects might be. Our understanding of the effects of the printing press is so multifarious that we can, and generally do, apply the figure as a placeholder for the unknown. By comparing changes in our information culture to changes that the printing press “created” in an earlier information culture, we open our claim to include a wide range of possible meanings, but in the process we drain the comparison of specific value. Second, and more importantly, by unreflectively using the printing press as a metaphor for changes in an information culture, we elide long-term shifts in ideology and material practice that may represent the most important forms of difference among various media systems.

Elyse Graham, “The Printing Press as Metaphor” (2016)

In this talk I want to resist narrating the digital age as a radical historical rupture, insisting instead that programming be considered within the continuum of textual production and labor that has long been the primary subject of book, literary, and media historians. Indeed, I will not consider the printing press itself at all, nor its attending narratives of information revolution. Instead, I will hone my attention to the processes of composition, imposition, and printing that constitute (some) of the labor of textual production in the broader letterpress system. Through such focus I seek to avoid some of the anachronistic dangers Graham outlines, striving instead toward Alan Liu’s vision of “a poiesis of digital literary studies able to imagine how old and new literary media together allow us to imagine.”

I. Letterpress as Craft

Let’s begin thinking about the craft of letterpress using a quote from a well-known article challenging the digital humanities, Adam Kirsch’s 2014 piece in the New Republic. In the passage I quote here, Kirsch asks of the “distinctive skills” required for digital humanities work, “are they humanistic skills?” In answer, he asks another, presumably rhetorical, question: “Was it necessary for a humanist in the past five hundred years to know how to set type and publish a book?” Kirsch seems certain the answer to his question is, “of course not,” but if we consider his question historically, the answer becomes, “absolutely, yes.” Writers and humanists in the past 500 years were often trained in printing or publishing—a great many knew precisely how to set type and publish a book—while a great many others understood the material processes of print well enough to reflect on, interrogate, or satirize them.

While preparing for this talk, I asked the book historians in my Twitter network to send me their favorite examples of writers consciously engaging with the materiality of print. I received so many suggestions I cannot list them here, but I compiled a Storify of the conversation for those interested in the many examples my colleagues provided, and even this long twitter thread barely scratches the surface of writerly engagements with print culture. We might think first of those who were in fact printers, such as Ben Franklin, William Blake, Walt Whitman, or William Morris. Franklin suffused his writing with metaphors drawn from the technologies and business of the hand press, as does Whitman in his poem, “A Font of Type”:

This latent mine—these unlaunch’d voices—passionate powers,

Wrath, argument, or praise, or comic leer, or prayer devout,

(Not nonpareil, brevier, bourgeois, long primer merely,)2

These ocean waves arousable to fury and to death,

Or sooth’d to ease and sheeny sun and sleep,

Within the pallid slivers slumbering.Walt Whitman, “A Font of Type,” Leaves of Grass (1891-92), via The Walt Whitman Archive

Whitman, who worked at various times as a compositor and editor for several newspapers, describes the “pallid slivers” of type in its case as a “latent mine” of “unlaunch’d voices” that can, though “primer merely” (a designation of type size roughly equivalent to the modern 10 point), summon either fury or peace. Whitman’s ode to type might put us in mind of humanist-printers who used their craft expertise to craft deliberate works of art.

We might also consider William Blake’s “infernal method” of printing, which he saw as necessary to execute his vision, or Morris’ Kelmscott Press, which produced elaborate editions of classic literature (or those Morris wished to make classics). In the nineteenth century, a good many writers were also employed as editors, particularly if we look beyond the few canonized writers who were able to support themselves entirely through literary production. Nineteenth-century newspapers are suffused with jokes, aphorisms, and poems that drawn from—and thus assume readers’ familiarity with—the technical details of print shop labor.

Even beyond humanists specifically employed in printing, a significant portion of academic and artistic writers were, by choice or by necessity, deeply knowledgeable about the processes of composition, imposition, and printing that committed their words to paper. Evidence of this widespread knowledge suffuses books well through the twentieth century (and we could compile contemporary examples of authors commenting on digital publishing as well). We might cite, for instance, Anne Bradstreet writing a poem addressed to the book she “Made…in rags, halting to th’ press to trudge;” or the typographical and material experiments in Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy; or Jane Austen writing to her sister Cassandra about “those enormous great stupid thick quarto volumes which one always sees in the breakfast parlour,” concluding “I detest a quarto” and championing the octavo; or the cetology chapter of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, in which classifies whales into the categories folio, octavo, and duodecimo, omitting the quarto because its shape is not sufficiently long to resemble a whale’s body; or we might cite the very long history of pattern poetry, which through its form comments on the materiality of type, spacing, and textual production. These are only a few examples of the ways writers reflected on or experimented with the technical processes which brought their writing to readers. The fields of bibliography and book history demonstrate again and again how understanding the technical, social, and economic realities of textual production can illuminate the literary, political, and sociological meanings of books.

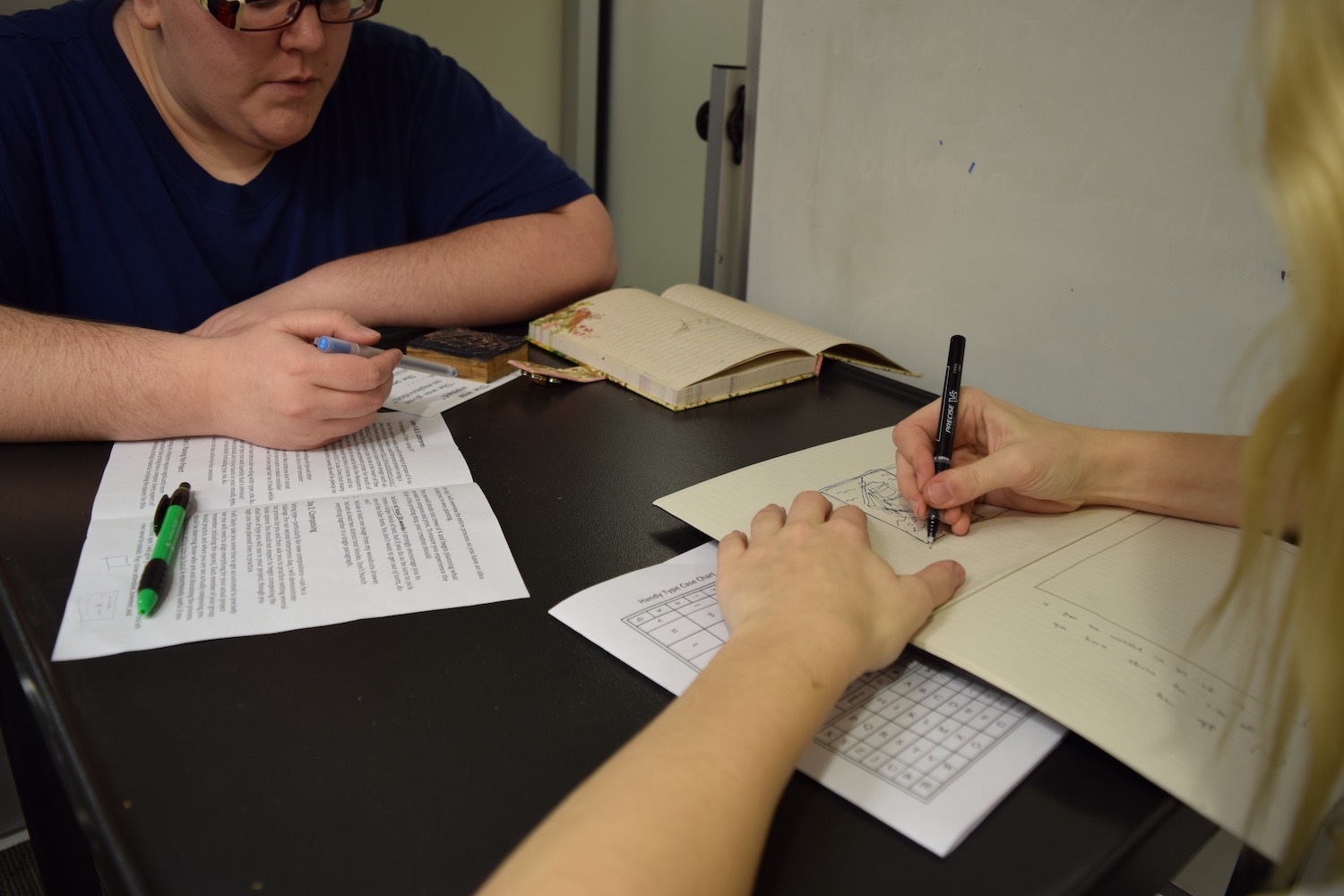

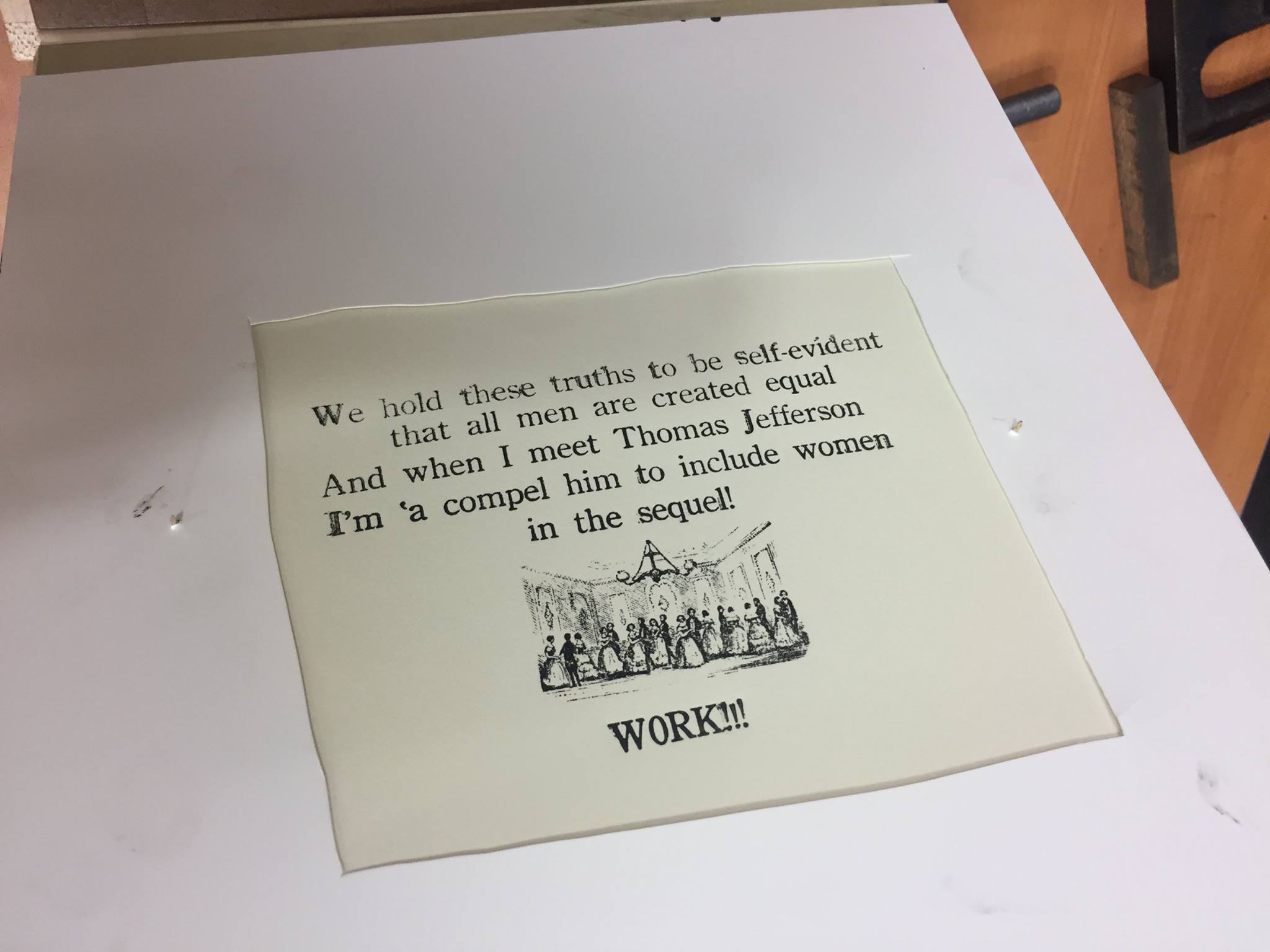

My students learn much about the processes of letterpress production by reading such book historians, but my “Technologies of Text” class proposes that, perhaps, the perspectives of compositors and printers can be best understood from the perspectives of compositors and printers. Using a somewhat ragtag collection of types and images I have assembled, I ask my students to learn about print by bringing a small printing project—a card or a pamphlet—from conception to execution. Working through this experience—and “work” is an important, operative word here—proves quite distinct from what my students typically do in English classes. They report that composing type and printing feels different, that it requires a discrete kind of thinking from that required for reading and writing. One student described it in spatial terms, as requiring the same part of their brain they use to assemble puzzles.

For those who have never worked on a printing press, it’s worth describing how the experience conjoins considerations about an abstract “text” with considerations of materials, geometry, and even—quite literally—pressure. Students can choose among the types (and type sizes) that I own, but only these, just as editors and compositors would choose from among the types owned by their print shop. Each font—a word which refers to the style of lettering but also the precise size—is contained in a wooden drawer, and these drawers describe aesthetic limits for any particular project.

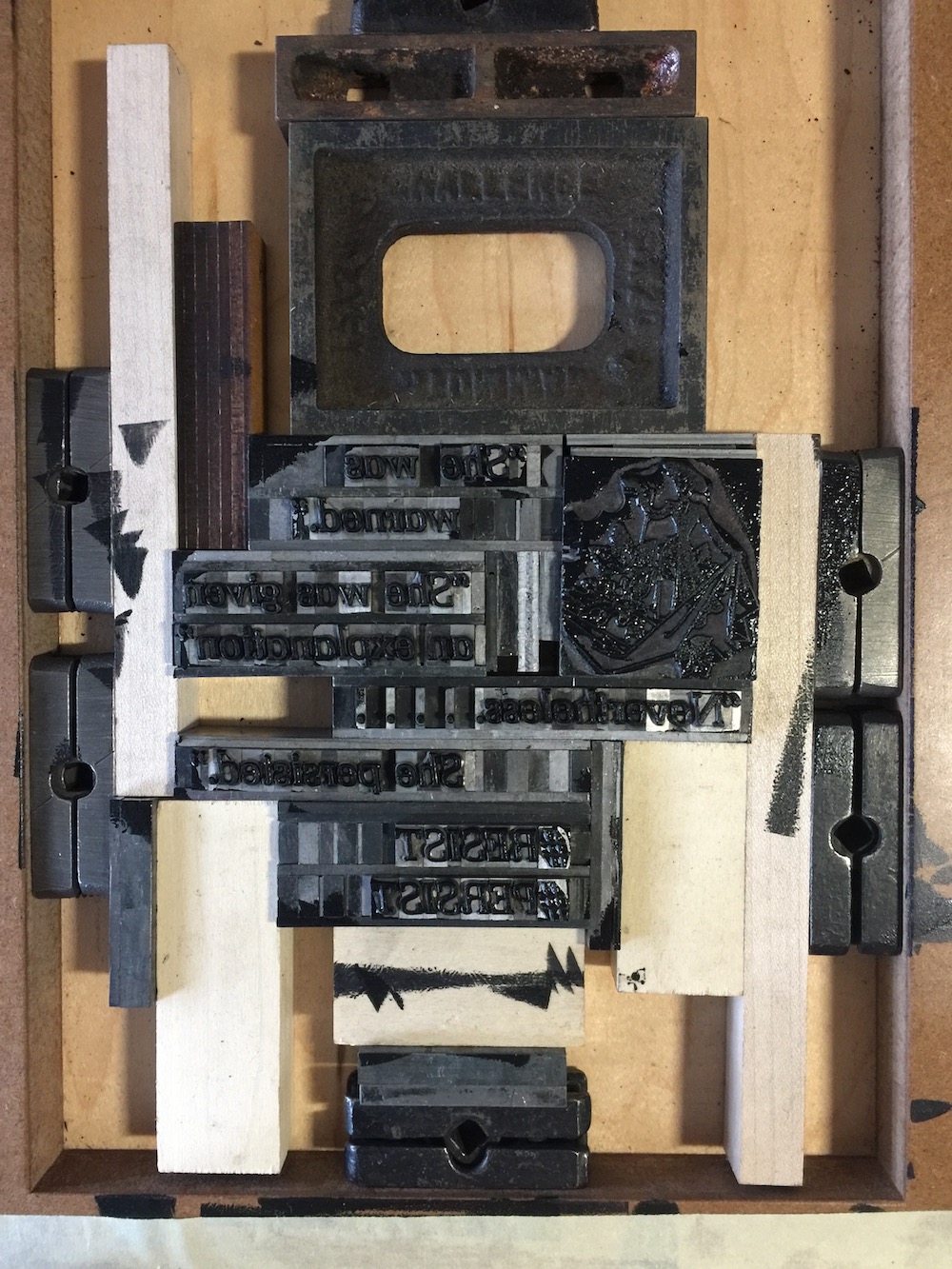

Once a font is chosen, students must compose the text, which means to assemble the letters using a composing stick. They must do so upside down and backwards, and the must keep in mind the eventual size of the layout on their chosen page, so that they compose lines of the correct length. These lines must eventually be assembled in a printers’ frame, along with woodcuts of images they hope to include in their print.

At this point students use furniture—pieces of wood or metal in a variety of sizes and (rectangular or square) shapes—to fill in the spaces between the edges of what they want to print and the frame. Then they use quoins—either wooden wedges or spring-adjustable metal devices—to “lock in” the type and images so they will not move under the pressure of the press. Before they can print, they also have to create a custom frisket—an ink-resistant sheet of paper with holes cut in it to accommodate the printing surface—to keep ink from marring the non-printing sections of the paper. After all this—and, frankly, I’m omitting a few smaller steps for time—they can finally print their text on my Book Beetle desktop screw press.

As when assembling a puzzle, print shop processes are often frustrating for students. Sometimes I don’t have a font that quite fits the mood they hope to convey. For students whose only experience of “font” is a drop-down menu with hundreds of immediate options, the physical limits of cold metal—including the weight of what I can transport from my office to our classroom!—can be difficult to adapt to. Sometimes they craft an elaborate plan that they cannot realize, as when an idea of mixing five or six fonts in a single project proves overwhelming to produce upside down and backwards. Sometimes their chosen image doesn’t quite fit, either with their lines of type or on the paper they chose. Sometimes the furniture doesn’t quite line up, or skews the text when the quoins are tightened because they haven’t distributed the pressure correctly across the frame. And sometimes we get all the way to pulling the press before they realize that a “q” was actually a “p,” or that their “w” is upside down and looks like an “m.” Through the printing process, in other words, students are confronted with the material realities that shaped textual production for hundreds of years. They don’t just read or hear about them, they experience them. They begin, in small but real ways, to understand the practices that defined the craft of printing: techniques for making texts fit, for marrying text and image, for conveying expression with limited components. They begin to understand the text as modular and physical, as something that must be executed as well as produced.

One of the more evocative asides in Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography might help us think about how the craft of printing differed, at least in the mind of one eighteenth-century printer-humanist, from the art of writing. Discussing his first printing master, Samuel Keimer, Franklin notes,

Keimer’s printing-house, I found, consisted of an old shatter’d press, and one small, worn-out font of English which he was then using himself, composing an Elegy on Aquila Rose, before mentioned, an ingenious young man, of excellent character, much respected in the town, clerk of the Assembly, and a pretty poet. Keimer made verses too, but very indifferently. He could not be said to write them, for his manner was to compose them in the types directly out of his head. So there being no copy, but one pair of cases, and the Elegy likely to require all the letter, no one could help him…Keimer, tho’ something of a scholar, was a mere compositor, knowing nothing of presswork.

There are two things worth noting here. First, Franklin clearly separates at least two crafts related to textual production: composition and presswork. Elsewhere in his Autobiography Franklin brags of his own proficiency in both, but he regularly describes colleagues trained in one or the other, such as Keimer. More enticingly, however, in this passage Franklin bifurcates writing and composing. Though he acknowledges Keimer is making an elegy, he resists calling that making process writing, which requires for Franklin a manuscript copy, from which proof type is properly composed. For Franklin, printing and writing are closely related—hence his hesitation—but not identical.

In calling printing a craft, I seek to highlight its blending of creativity and technical specificity. The essential tools of letterpress printing were drawn, for most compositors and editors, from a limited set (e.g. type, furniture, composing sticks, etc.). Master compositors and printers passed on best practices for approaching texts of various kinds. Many of the day-to-day operations of the print shop were iterative and industrialized. Within this frame, however, printers produced artifacts of remarkable inventiveness and even beauty.

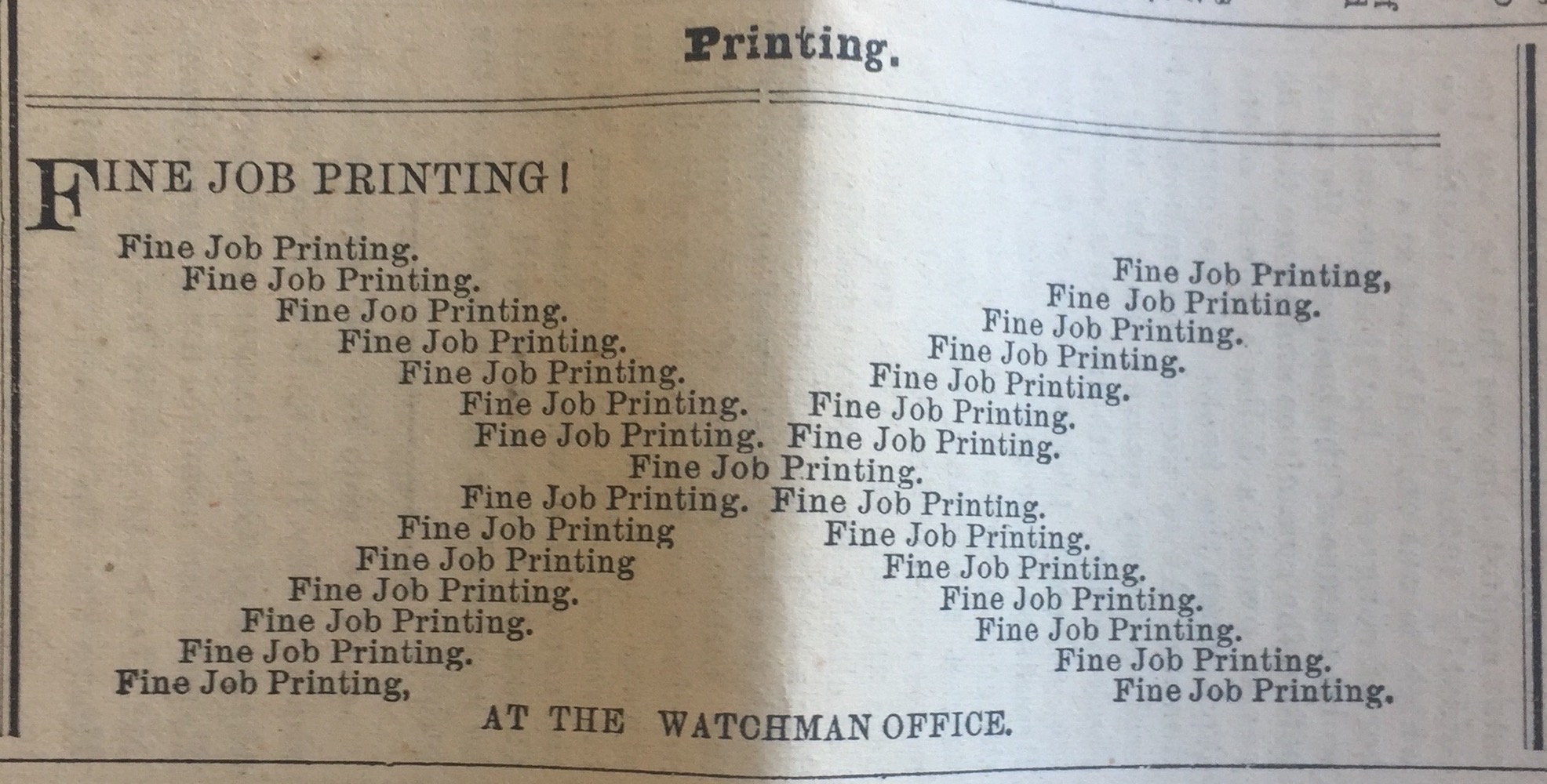

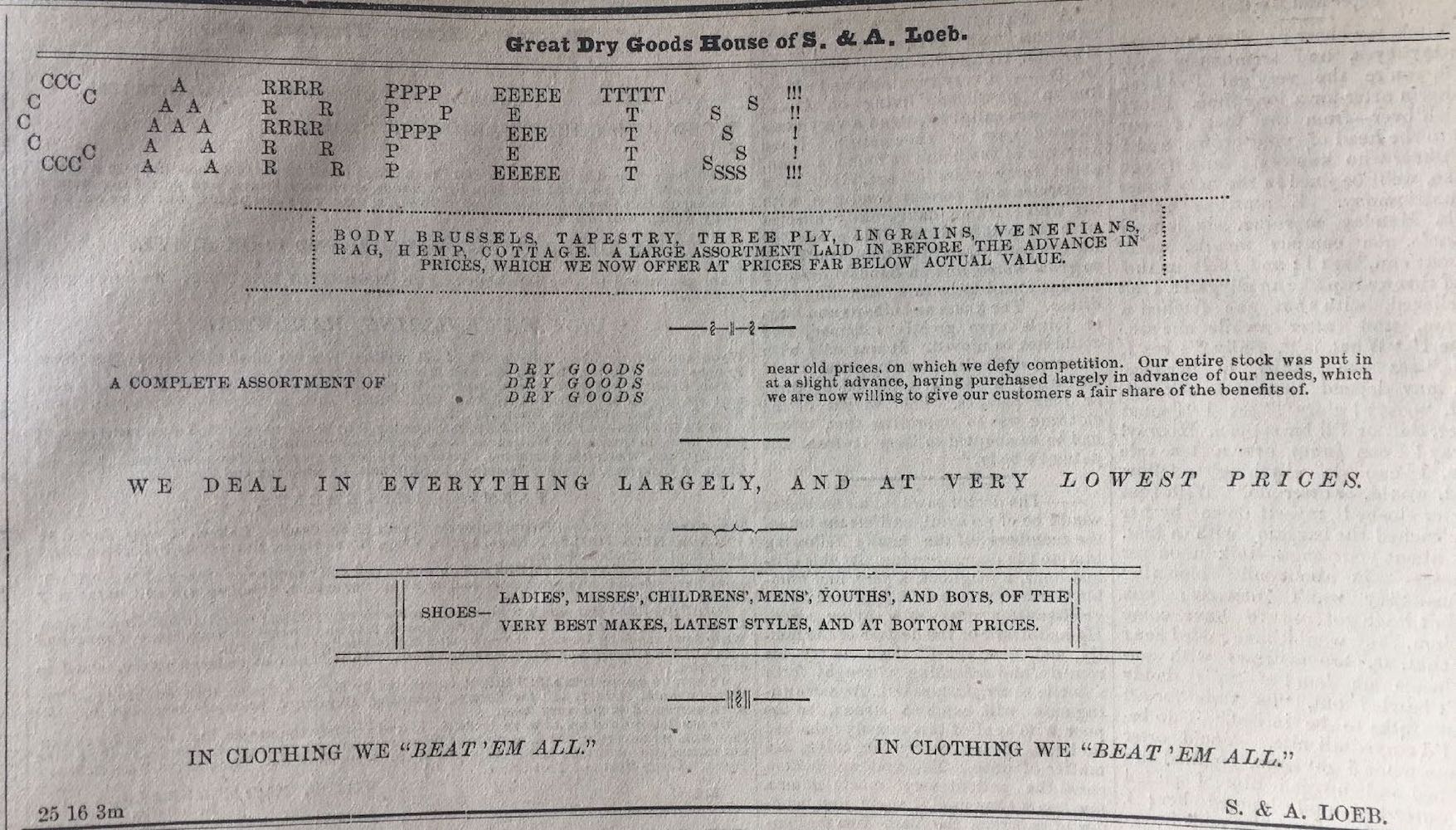

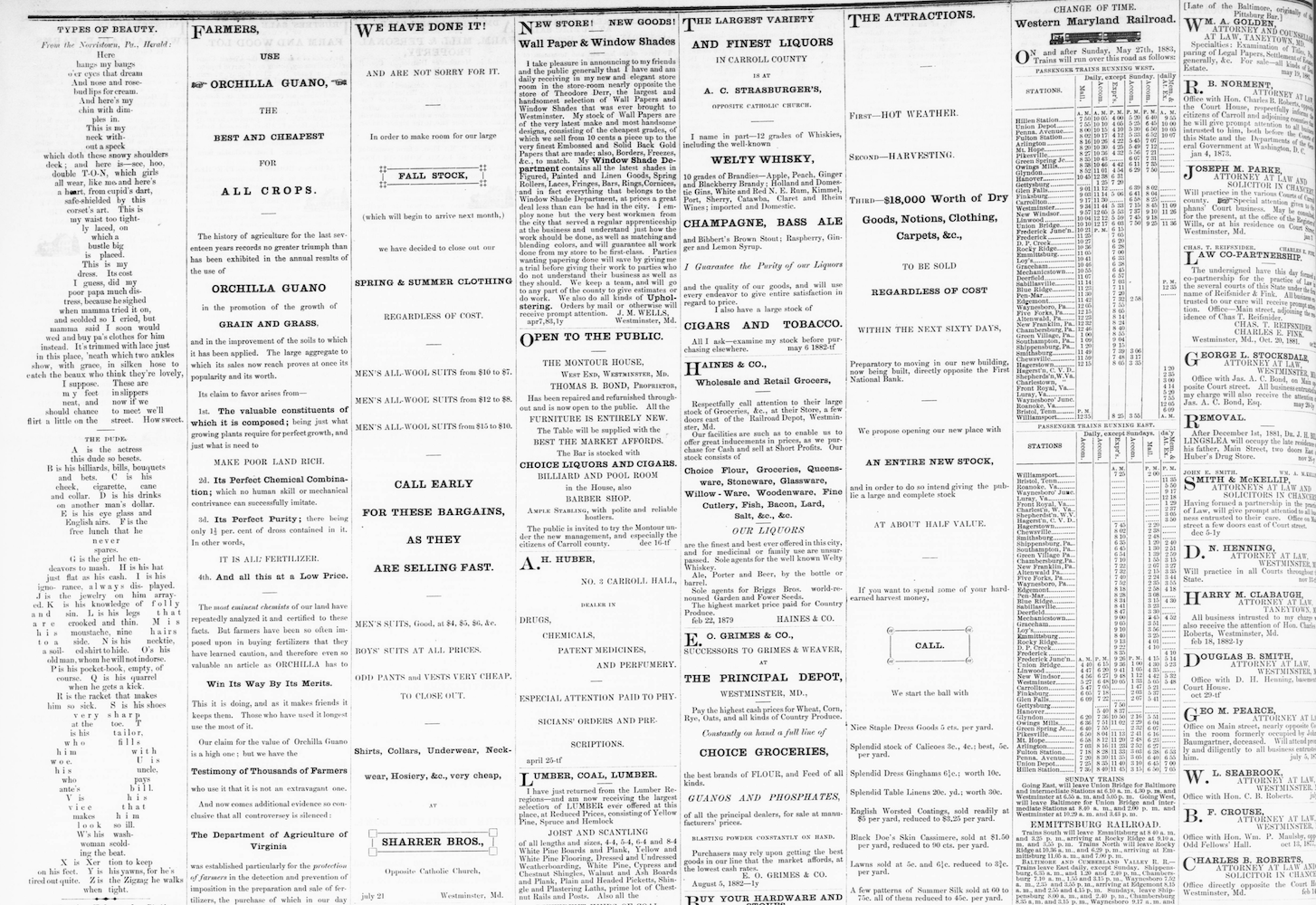

We can see this inventiveness even in the most quotidian of printing environments, the nineteenth-century newspaper. Often compositors found the most leeway for creativity and play in typesetting advertisements, as in these examples. Note that “fine job printing” is advertised through a show of compositional talent. I’m particularly drawn to the large “CARPETS” drawn using smaller type (perhaps “primer merely”?), which resembles nothing so much as the ASCII art of the early internet.

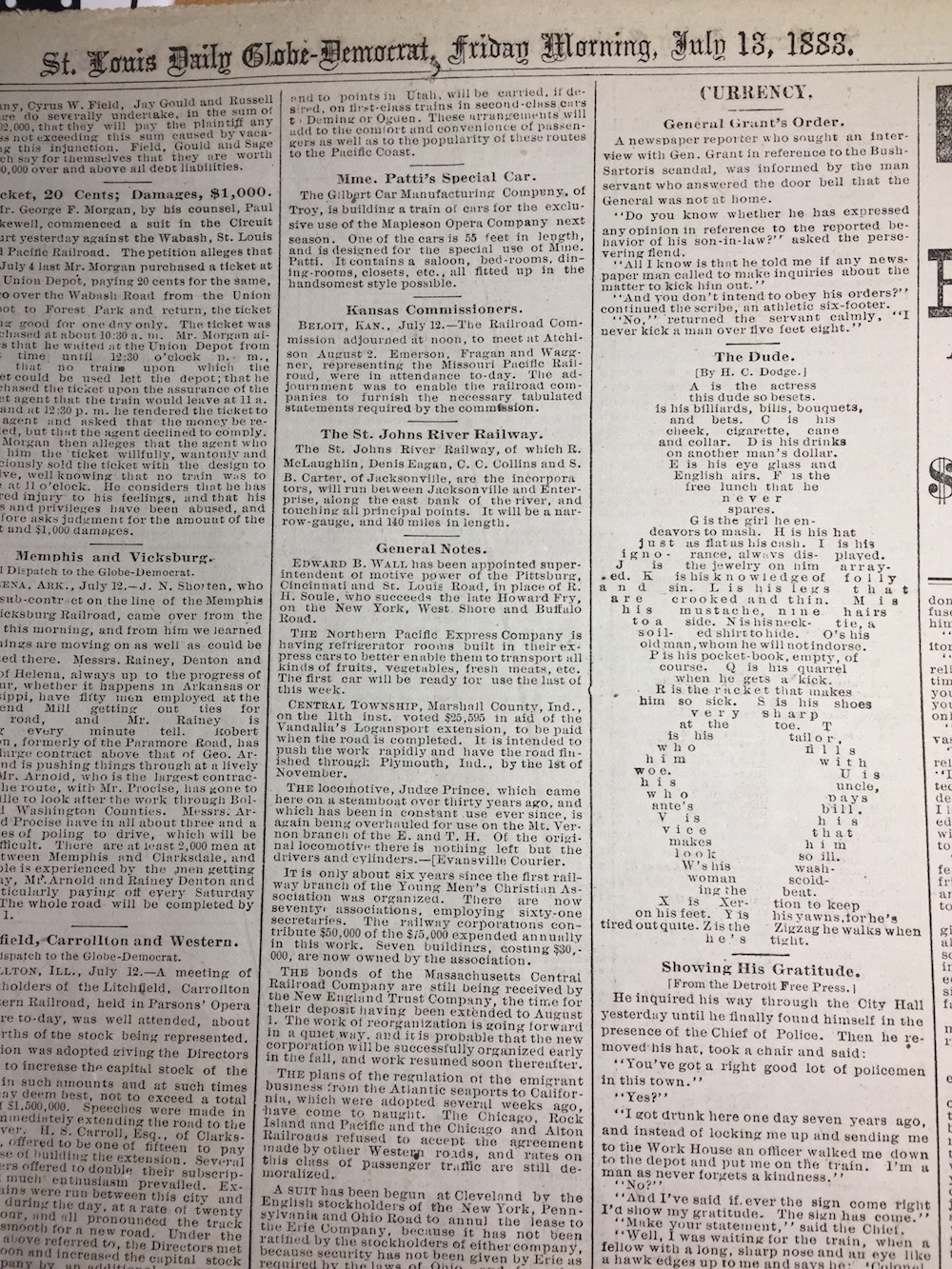

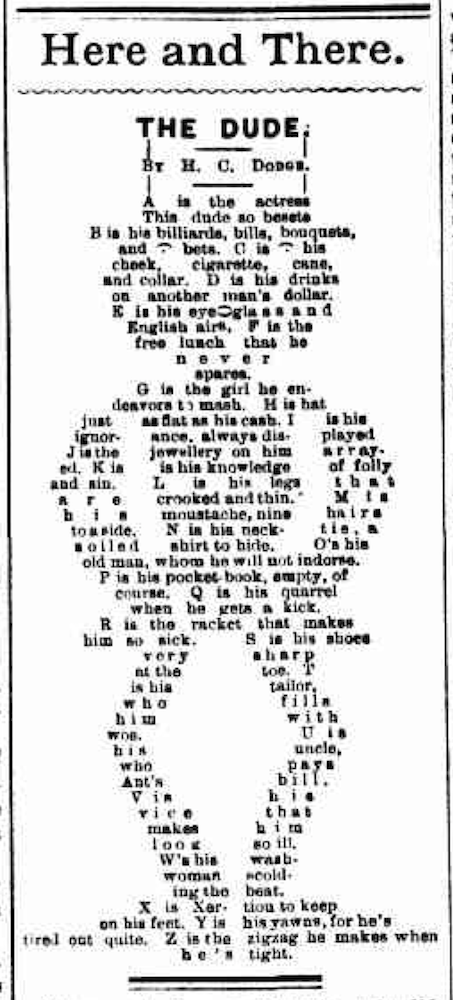

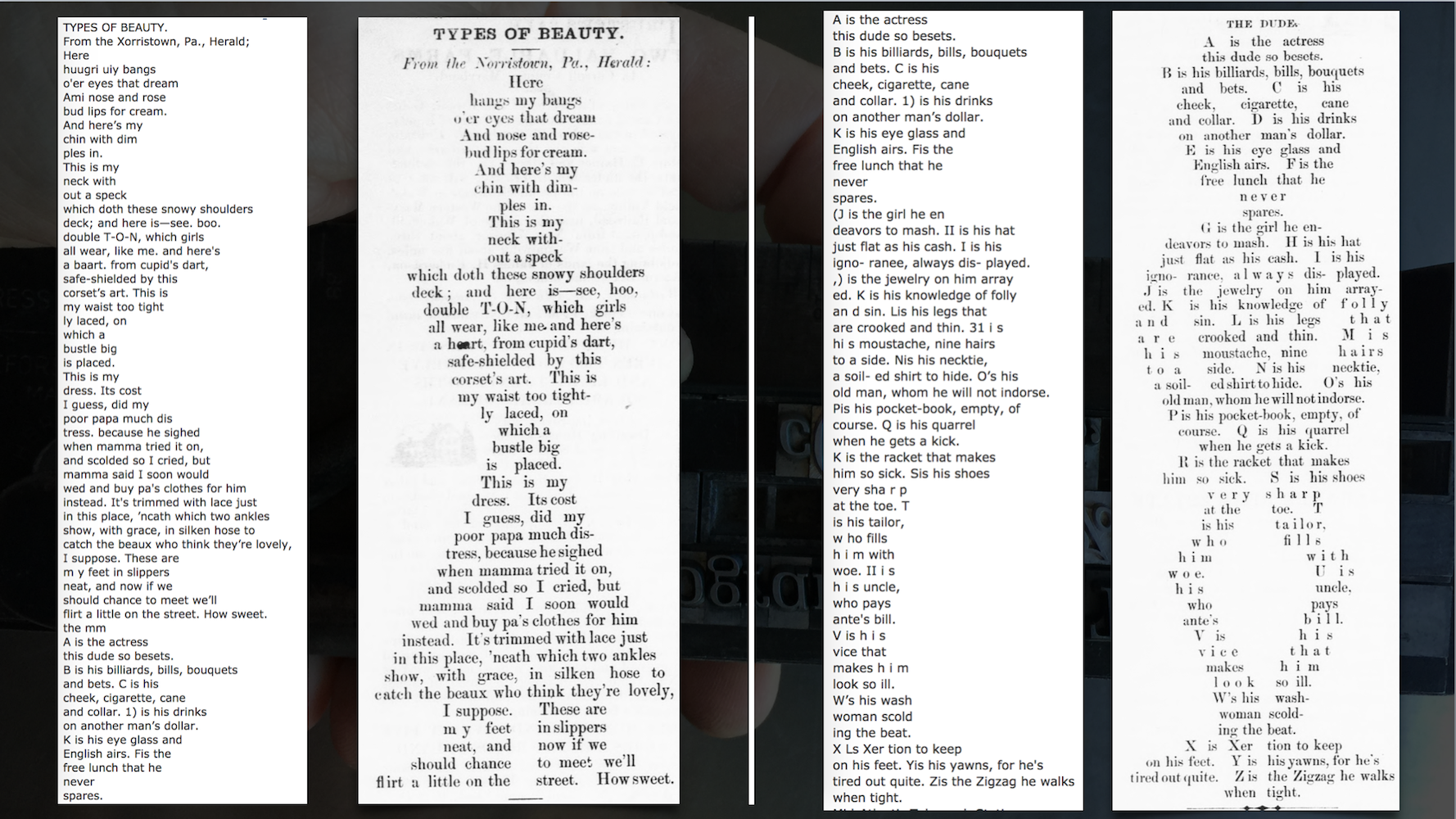

Occasionally, however, newspaper compositors turned their talents to other ends. Consider, for instance, “The Dude.” I first found “The Dude” in a print edition of the St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat, which I have in a small collection of teaching artifacts.

For obvious reasons, I was taken with this pattern poem satirizing “a dude,” a word that referred in the nineteenth century to a city slicker and a dandy, and particular a city slicker who affected “cowboy” attire and slang.

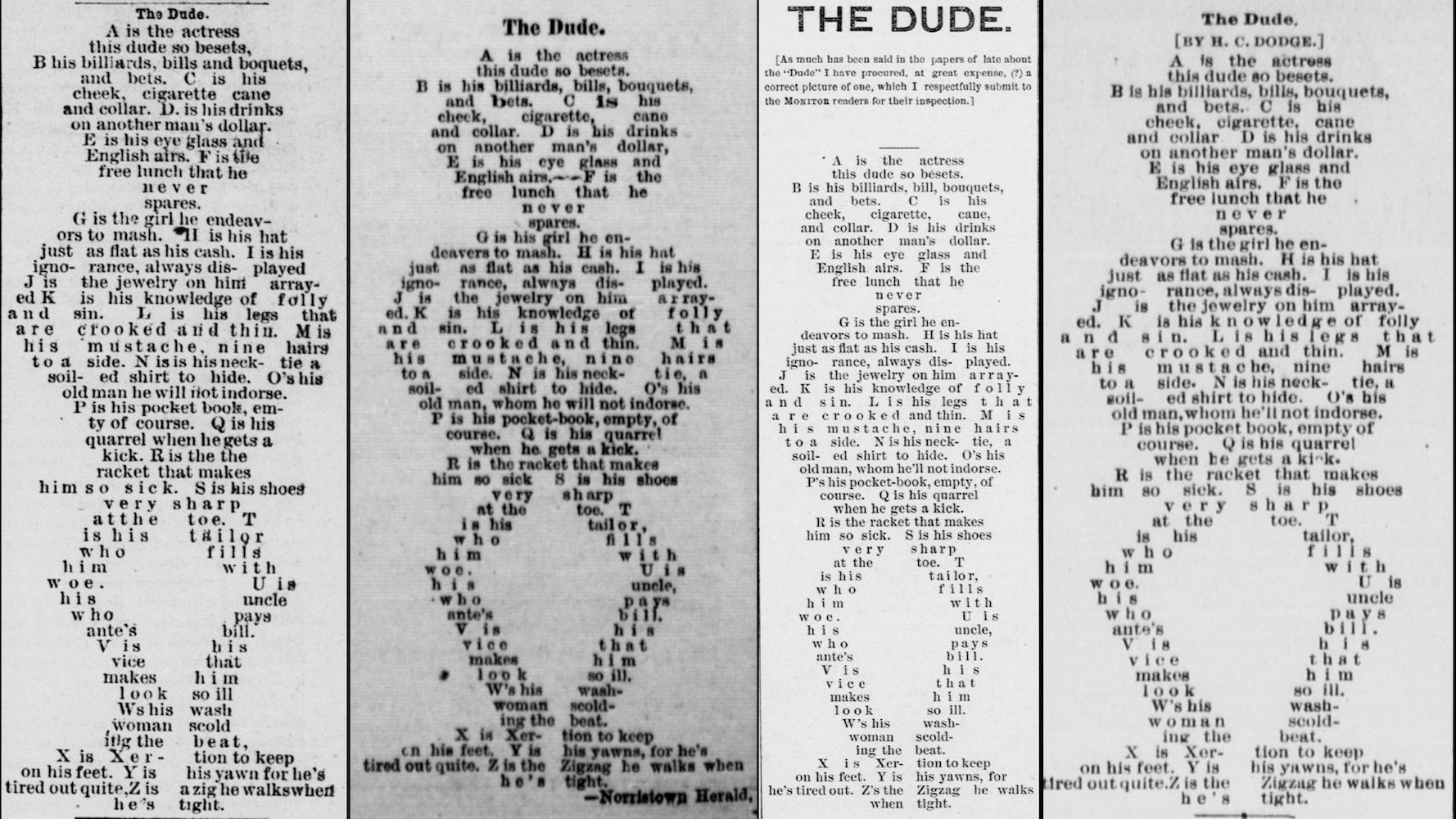

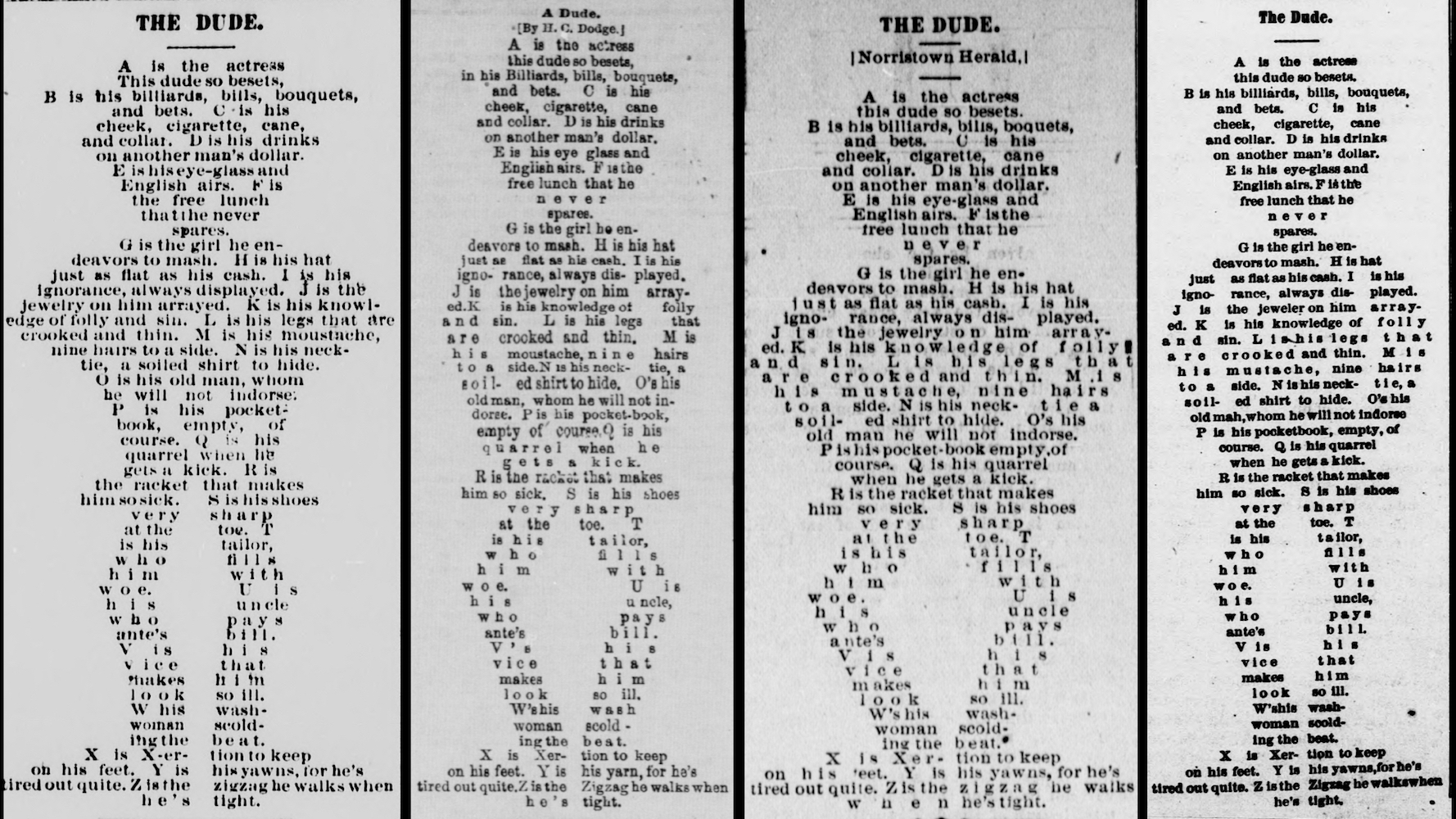

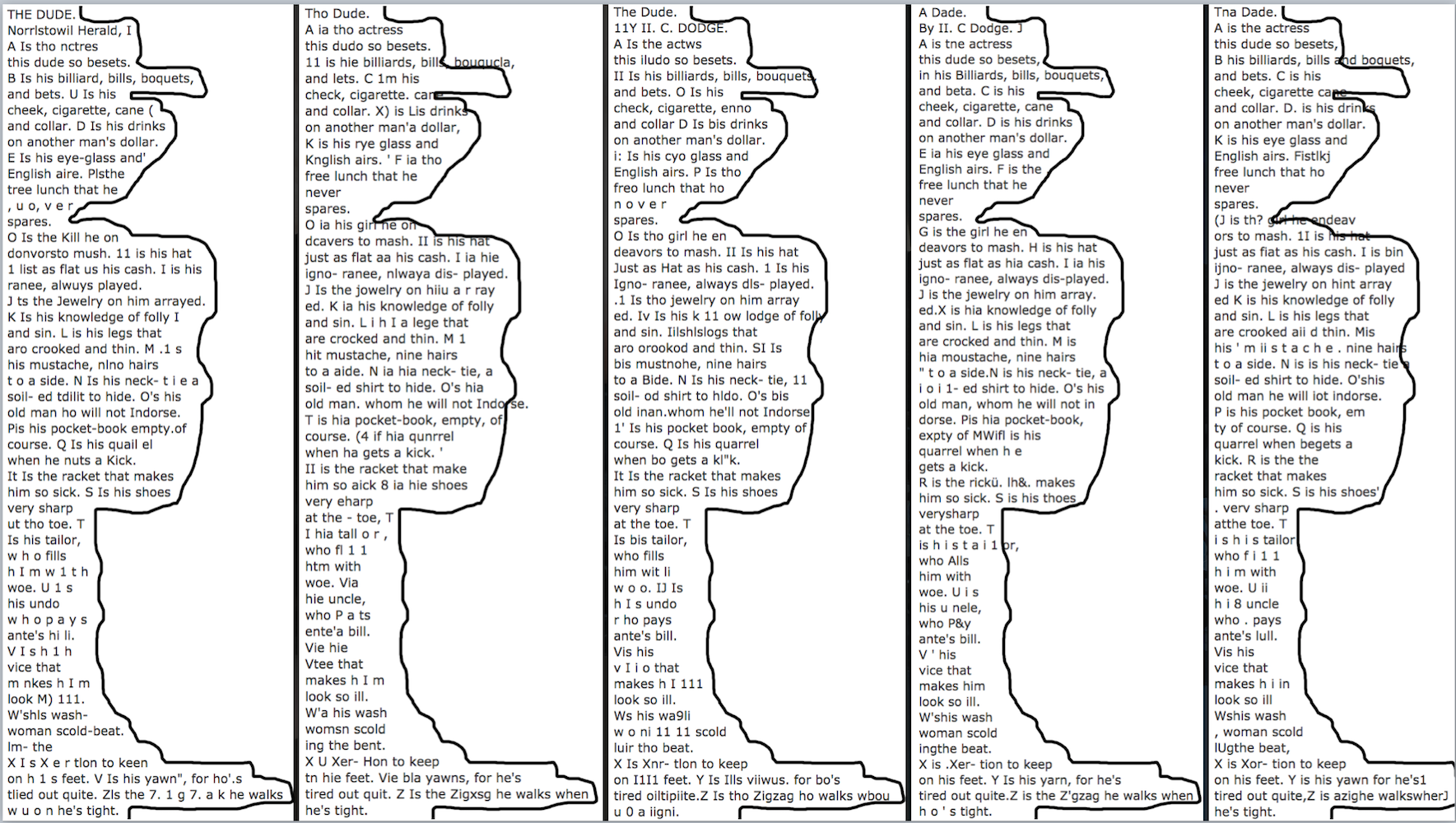

As “The Dude” circulated through nineteenth-century newspapers, it’s general shape remained the same, but the precise shape of the dude varied based on the type available to particular compositors, and their particular interpretations of his shape. I particularly love this Australian reprinting in the Darling Downs Gazette (27 Oct. 1883), in which the poem’s title and author are incorporated into the pattern, giving the dude an especially tall hat. The dude was eventually killed in type, too, his face somberly showing through a poetic death shroud.

I identify composition and printing as craft practices not to demean them—far from it—but to mark the specific modes of thought and labor they require. In particular, I highlight the formalism of printing. Translating a text from one’s mind into a physical artifact requires a series of concrete decisions that freeze language into a specific form. Moreover, that form can be mistaken, failing to work as it should. Printing is a craft insofar as its primary work involves adapting methodological and aesthetic conventions to the needs of specific projects and, quite often, adapting the needs of specific projects to the affordances of the available printing technology and materials. Ultimately, printing requires us to create a particular model of the text: a simplification of it, perhaps, in service of wider communication.

II. Coding as Craft

I want to pivot (temporarily) from “The Dude” to more contemporary meditations on programming and writing. First, however, I need to establish precisely what kind of programming I am talking about and outline why it, too, might best be considered a craft practice. To do that, we need to separate “coding” and “programming” from the discipline of computer science. As Stephen Ramsay helpfully reminds us, “computer science != programming.” To think of computer scientists as primarily interested in code, Ramsay insists, is akin to thinking of humanists as primarily interested in copyediting. Certainly copyediting is important for expressing our ideas, as programming often is for expressing the ideas of computer scientists, but we would never consider copyediting our primary work. Likewise,

Very few computer scientists…are concerned with building tools of any kind. The ones who do build things are mainly doing so to demonstrate some theoretical idea or to prove the viability of a (presumably novel) engineering principle. The concrete tools that sometimes emerge from these efforts (compiler generators, programming languages, theorem provers) are mainly side effects of some more abstruse intellectual activity. The vast majority are not in it to create software […]

Stephen Ramsay, “DH and CS” (2013)

Designing a new algorithm or engineering principle is a creative and intellectual act, and much of the work which happens in computer science departments—which in general humanists understand poorly, if at all—and should thus be understood as theoretical and intellectual work.

As Annette Vee argues in her new book Coding Literacy, “neither programming nor CS is well served by the idea that they map perfectly onto each other” (41). For Vee, the conflation of programming with CS severely limits our ability to imagine how programming might be useful in other domains. Rather, she wants to consider the relationship between programming and writing, which resist simple one-to-one comparisons:

Programming has a complex relationship with writing…Programming is writing because it is symbols inscribed on a surface and designed to be read. But programming is also not writing, or rather, it is something more than writing. The symbols that constitute computer code are designed not only to be read but also to be executed, or run, by the computer. So, in addition to being a type of writing, programming is the authoring of processes to be carried out by the computer…computer code is simultaneously a description of an action and the action itself (20).

It is in this conceptual gap that I think composition and printing can be useful metaphors for programming. As Franklin insists of Keimer, composing type is not writing, per say, though it employs similar symbols—in mirror image—to those which people read. We might think of composition, imposition, setting forms of type, and so forth as the authoring of processes to be carried out by the press. As with code, those processes can fail to execute, or fail to execute correctly. There are right and wrong answers in printing as there are with programming. Likewise programming carries a strong association with writing, and indeed often carries writing itself, but is not only writing.

In another series of labs for my “Technologies of Text” class, students learn the basic building blocks of computational text analysis using the R programming language. They tinker with code that will load textual data, count words or ngrams, compare word usage among books, or build a concordance. More creatively, they conceive and code Twitter bots that remix poetry or other kinds of literature. To do this, they learn the basic grammar and syntax of R and begin experimenting. They do not write wholly original code or design new algorithms. Instead, they begin with a model bot I have coded (which itself borrowed much from other coders), change small sections of code, perhaps move some of the code chunks around, and see what happens. The process is halting, recursive, and iterative. They do find space for creativity in this activity, but that creativity must operate within the structural and operational constraints of the programming environment and, frankly, within the constraints of their burgeoning understanding of R.

As with printing, students report a different intellectual engagement with programming than with reading and writing. There a spatial quality here, too, as programming is more procedural than writing—first this happens, then that happens, and hopefully at the end everything runs as you expect. To output something we might recognize as creative, such as a poetry bot, students have to consider the formal properties of both the poetry they wish to remix—e.g. what are its parts of speech? how many syllables are there per line?—and the formal properties of the code—e.g. what parts of speech can I retrieve using the Wordnik API? how many characters can I output to Twitter? They must consider how the formal properties of poetry and programming will relate: e.g. will any verb retrieved from Wordnik fit this poem, or do I need to introduce additional constraints about tense, length, and so on?

In adapting existing code to meet their creative or analytical needs, students engage with programming as a craft practice. The work within an existing infrastructure and adapt it in small ways to meet the particular needs of their projects. In other words, they engage with programming in ways quite consonant with most humanists—and, indeed, most scholars from non-CS fields—who are engaged with computation. We borrow, reorganize, and adapt; we build on existing practices. As Ramsay notes later in “DH and CS,” “Programming…is a craft skill—a practical matter of getting digital devices to exhibit particular behaviors. This is not to imply that it’s a simple thing; anyone who has done it seriously knows that it is a ferociously complex thing. But then again, so is writing.” Programming is increasingly a craft that can be adapted across many domains. Its components—the functions and loops we copy and arrange, are perhaps analogous to the type, leading, furniture and so forth that printers adapted for expressing writing across many domains.

In saying this, I don’t want to downplay the work of humanists engaged with computation at more fundamental levels. There are certainly researchers who would be more rightly characterized as creating new computational methodologies, in direct conversation with fields like CS. To stretch my metaphor a bit, we might think of those folks not as compositors or printers, but as the engineers who developed new printing technologies (the steam press, say, or the Linotype). Nor do I wish to place humanistic programming in a subservient role to quote-unquote “real” computational work happening in other disciplines. In fact, my goal is quite the opposite. Like writing, I want to insist that there are many levels at which we might engage programming. I want to advocate for as broad and multi-faceted engagements with programming practice as we can trace with print culture in earlier periods. By thinking of programming as a craft practice, I hope to show that the barrier for entry need not be a degree in computer science. If we are, as Cathy O’Neil argues, increasingly subject to “weapons of math destruction” that influence all aspects of our lives from our educations to our health insurance, we need a more broadly suffused understanding of how programs operate and, most essentially, a more diverse group of people thinking about how they might operate.

For my humanities students, this is the primary reason I encourage them to understand programs, whether or not they are interested in becoming programmers. Like those authors who could turn their knowledge of print shop practices to good—or subversive—use in crafting their works, I want my students to be engaged and critical users of the computational technologies that pervade their world. I largely concur with my colleague, Benjamin Schmidt, that “digital humanists do not need to understand algorithms at all. They do need, however, to understand the transformations that algorithms attempt to bring about.” In other words, we don’t all have to become mathematicians or statisticians to engage meaningfully with computation. We do need to understand the logic of any code we adopt or adapt, however, so that we can account for the transformations on which we base our critical or creative work.

I anticipate (at least) one strong objection to this line of thought. Given that programming largely thrives in domains outside the humanities, and commercial domains in particular, do we not risk diluting humanistic training with methods that aren’t just not humanistic, but perhaps anti-humanistic? I suspect this fear is at the heart of Kirsch’s critique, with which I began section one. However, I would suggest that such a view requires a nostalgic and ahistorical understanding of prior communications technologies, such as print. We look back at print culture and see only books, which makes it quite easy to think of letterpress as a largely humanistic technology. As scholars such as Lisa Gitelman, Leah Price, and others remind us, however, the vast majority of letterpress work comprised government documents, blank forms, currency, religious or political pamphlets, handbills, lottery tickets, and many other species of “cash on the barrel” printing. These print genres occupied the majority of most printers’ days and provided a majority of the income that supported less secure jobs such as books.

In the latest issue of Common-Place, Paul Erikson encourages “Thinking about books as objects that were processed, stored, and packaged by industrialists.” Focusing on the eighteenth-century American printer Isaiah Thomas, Erikson seeks to reorient attention toward books not as exemplars of abstract texts, but instead as “manufactured goods that drew on the Atlantic world trade in raw materials, such as the rags Thomas bought for his mill, gold, and leather, and in tools, such as composing sticks and type, which represented Thomas’s single biggest capital asset.” Books are objects of affection, memory, and even desire, which is to say they are objects easily romanticized. Contemporary letterpress printing is now distinctively “old fashioned” and “artisanal” in ways that can distort our historical view. The deep cut of the type in a modern letterpress wedding invitation, for instance, is a product of our own time, as a fine printer in the actual letterpress period would consider such deep impressions as markers of poor quality. Printing in the hand press period was a commercial and industrial endeavor. Indeed, the benefits of print over manuscript were expressed in terms of speed, and scale, and reproducibility of work. By considering programming as a craft akin to printing, perhaps, we can better situate the kinds of programming we do for research and creative expression in the humanities among the many other uses to which programming is put in society at large. Printing was a primarily economic technology that produced essential artistic and humanistic texts. Programming can do the same.

On the other hand, I want to insist that considering letterpress printing and contemporary programming as craft practices does not require us to lionize either. Book historians have done much work demonstrating how the logic of print served colonial and racist ideologies, and how the operations of print culture worked to marginalize minority voices. Likewise, scholars of computation have interrogated the exclusionary logic of various programming languages as well as the research or corporate cultures from which they emerged. Indeed, these logics are entwined both practically and metaphorically, as indicated by everything from the layout of the computer keyboard (based in large part on the distribution of letters in printers’ type cases) to the skeuomorphic language and graphic elements of computer interfaces (even in text-based programming languages, “print” is the command to display something on the screen for a human reader).

Our contemporary, digital textual technologies are deeply imbricated with their forebears. In her article about print-on-demand editions of John Milton, Whitney Anne Trettien encourages us to “imagine mediation as the process of constructing history out of history,” recognizing the ways that print and digital mediations of texts interact with each other across a textual history. These processes can be traced in digitized newspapers as well. In the remediation from print to digital, the object of scholarly inquiry changes—the digital newspaper is a new edition of the text—but that new edition carries, to gloss Bonnie Mak’s “Archaeology of a Digitization”, palimpsestic traces of its original we can visualize and analyze computationally.

The Viral Texts Project employs text mining techniques to identify widely-reprinted texts in nineteenth century newspapers. We began working with US newspapers, though we are also part of the new Digging Into Data project, Oceanic Exchanges, which will look at the global exchange of information in the period. To learn more about our methods, the genres of writing the project highlights, or the networks of influence it uncovers, see the project’s publications, which we link to on its website.

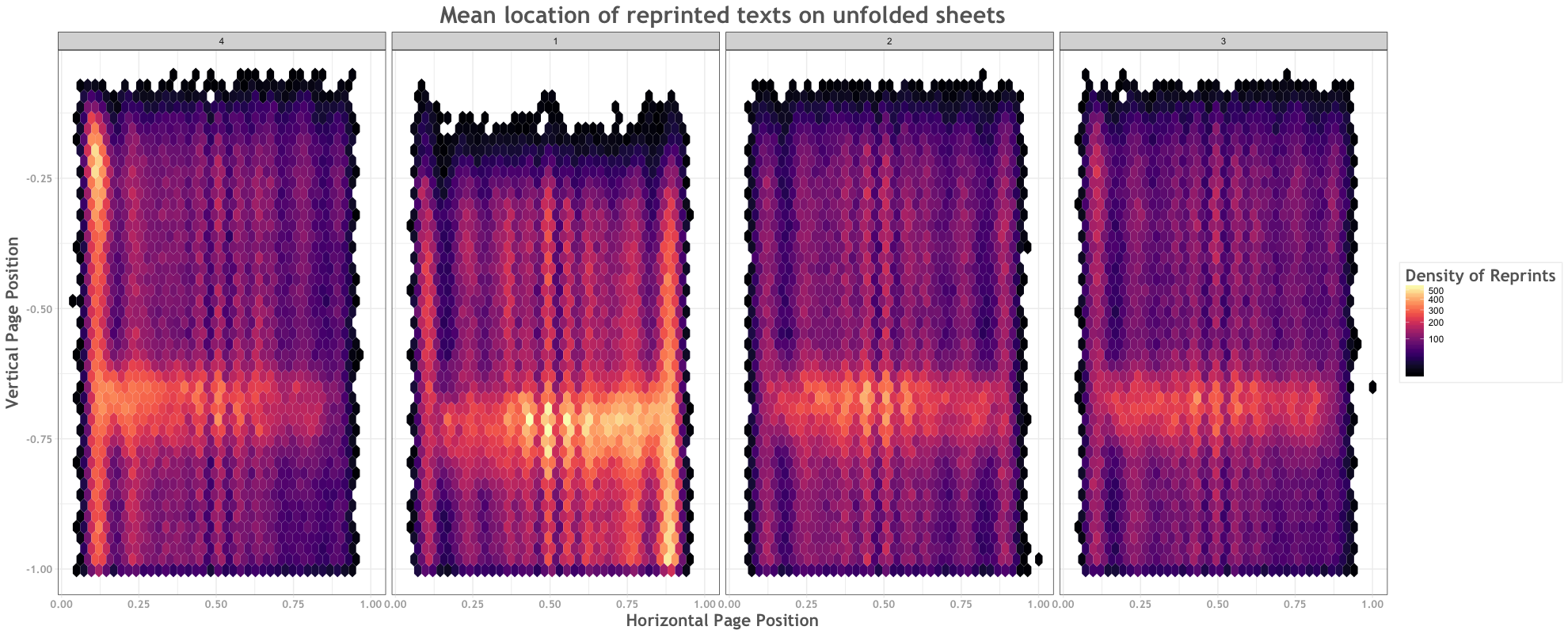

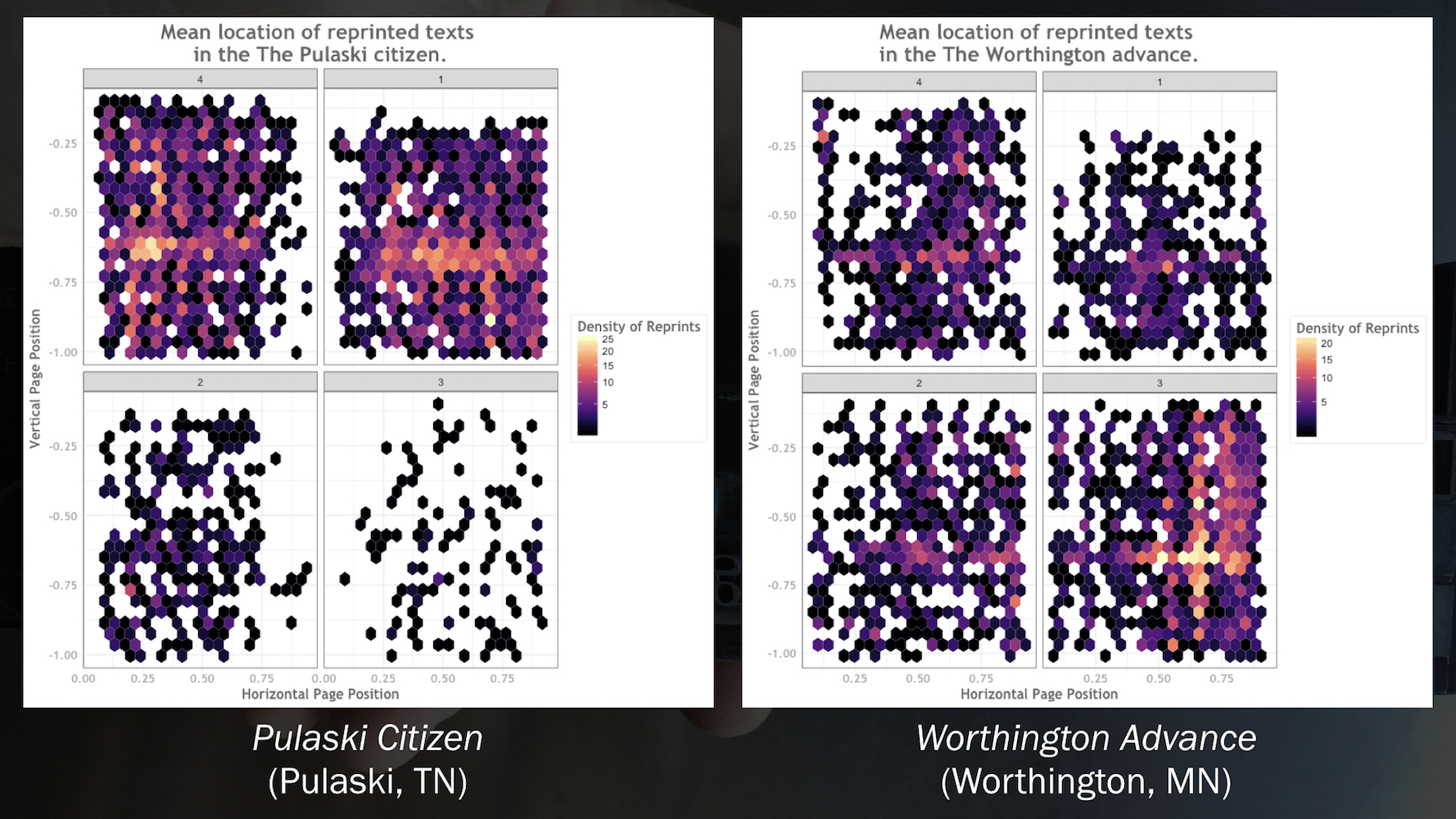

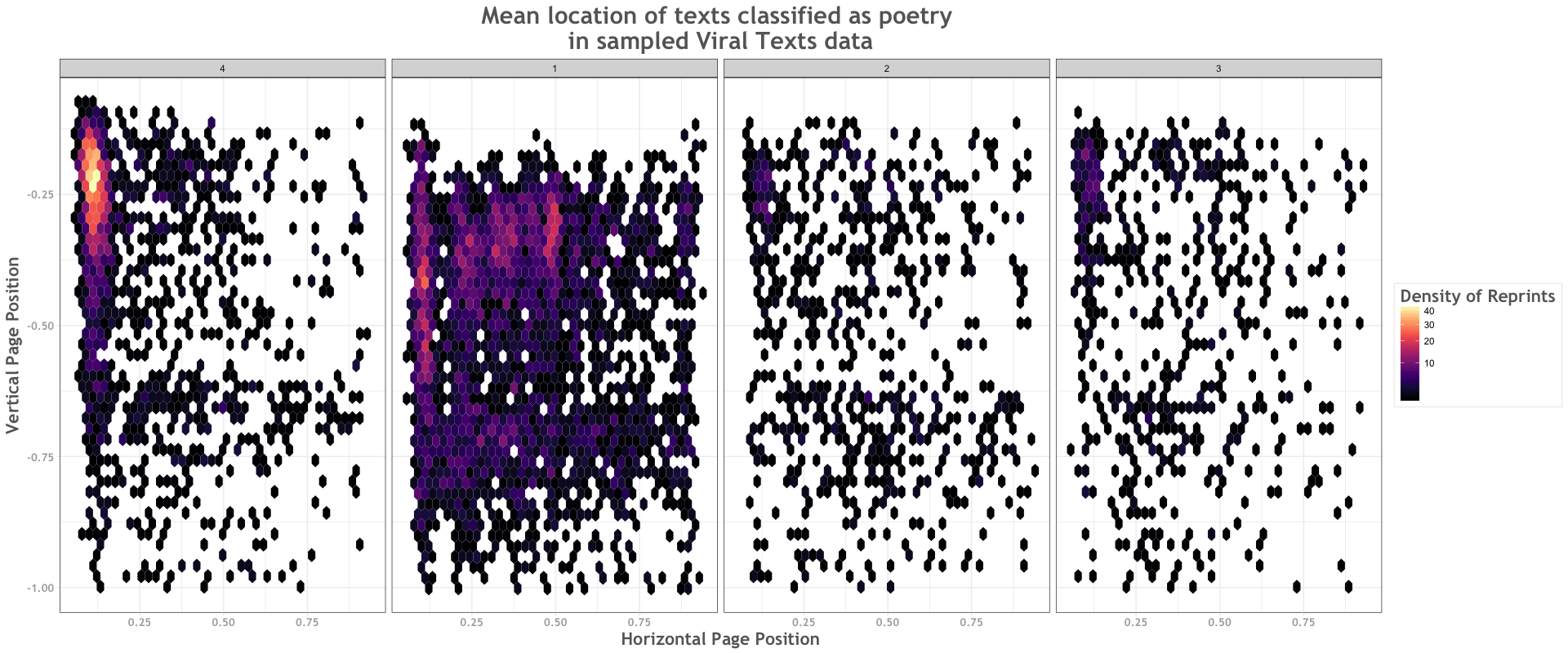

Today I want to talk about some more recent experiments, which are very much in progress, which is to say I can talk about the questions we are asking more than giving any answers. In short, however, we are using the locations of identified reprints—which in the newspaper data is expressed through X,Y coordinates—to map reprints back onto the newspaper page. Our goal is to illuminate the workaday practices of compositors and editors in the newspaper printing office—to better understand how they put the puzzle pieces of the paper together, and how they thought, practically and spatially, about its aesthetics and hybrid genres.

Where, for instance, did they put reprints? Most periodicals historians would tell you that reprinted content could mostly be found on pages 1-4, which made up the outer form of the typical four-page (or one double-sided sheet of paper, folded) paper, alongside other material left in standing type, such as mastheads and advertisements.

Our early layout experiments, however, indicate that local practices varied widely, and some nineteenth-century newspapers, such as the Worthington Advance, printed more original content on page one than their typical contemporaries. The modern front page, of course, is defined by carrying the most pressing material. One question we might ask, then, is which papers moved toward a modern front page first, and how did the front page evolve across the nineteen-century?

If we combine these layout analyses with the work of Viral Texts RA Jonathan Fitzgerald, who has been computationally classifying the genres in our corpus, we can also think spatially about particular genres. Where, for instance, did the typical nineteenth-century newspaper print poetry? And again, which newspapers varied from the conventions of the day?

I want to close by returning to “The Dude” to think in a more speculative mode about the palimpsestic qualities of the digitized text. In this issue of the Democratic Advocate (4 August 1883), “The Dude” appears below another pattern poem, “Types of Beauty.” In many ways, these poems seem uniquely resistant to computational analysis. Transcribed through OCR software, these poems will inevitably lose their defining feature, their shapes.

If we look at the OCR for these poems, however, we see (I believe) a shadow of the original poems. “The Dude” is still there, though perhaps in profile.

If we look at the OCR for a series of “The Dude” reprints, that profile seems quite consistent. Perhaps, in other words, the careful typesetting of nineteenth century compositors resonates through our imperfect digitizations. With the right program—a program yet to be crafted— we might be able to trace these patterns, too.

Notes

-

N. Katherine Hayles, Writing Machines, Cambridge: MIT Press (2002), 19, 15. ↩

-

Nonpareil, brevier, bourgeois, and long primer are each names for standard type sizes prior to standardization around the point system we still use today. In this list the sizes ascend, and the sizes listed are roughly equivalent to 6 point (nonpareil), 8 point (brevier), 9 point (bourgeois), and 10 point (long primer). ↩