Representing the “Known Unknowns” in Humanities Visualizations

Note: If this topic interests, you should read Lauren Klein’s recent article in American Literature, “The Image of Absence: Archival Silence, Data Visualization, and James Hemings,” which does far more justice to the topic than I do in my scant paragraphs here.

Pretty much every time I present the Viral Texts Project, the following exchange plays out. During my talk I will have said something like, “Using these methods we have uncovered more than 40,000 reprinted texts from the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America collection, many hundreds of which were widely reprinted—and most of which have not been discussed by scholars.” During the Q&A following the talk, a scholar will inevitably ask, “you realize you’re missing lots of newspapers (and/or lots of the texts that were reprinted), right?”

To which my first instinct is exasperation. Of course we’re missing lots of newspapers. The majority of C19 newspapers aren’t preserved anywhere, and the majority of archived newspapers aren’t digitized. But the ability to identify patterns across large sets of newspapers is, frankly, transformative. The newspapers that have been digitized under the Chronicling America banner are actually the product of many state-level digitization efforts, which means we’re able to study patterns across collections that were housed in many separate physical archives, providing a level of textual address not impossible, but very difficult in the physical archive. So my flip answer—which I never quite give—is “yes, we’re missing a lot. But 40,000 new texts is pretty great.”

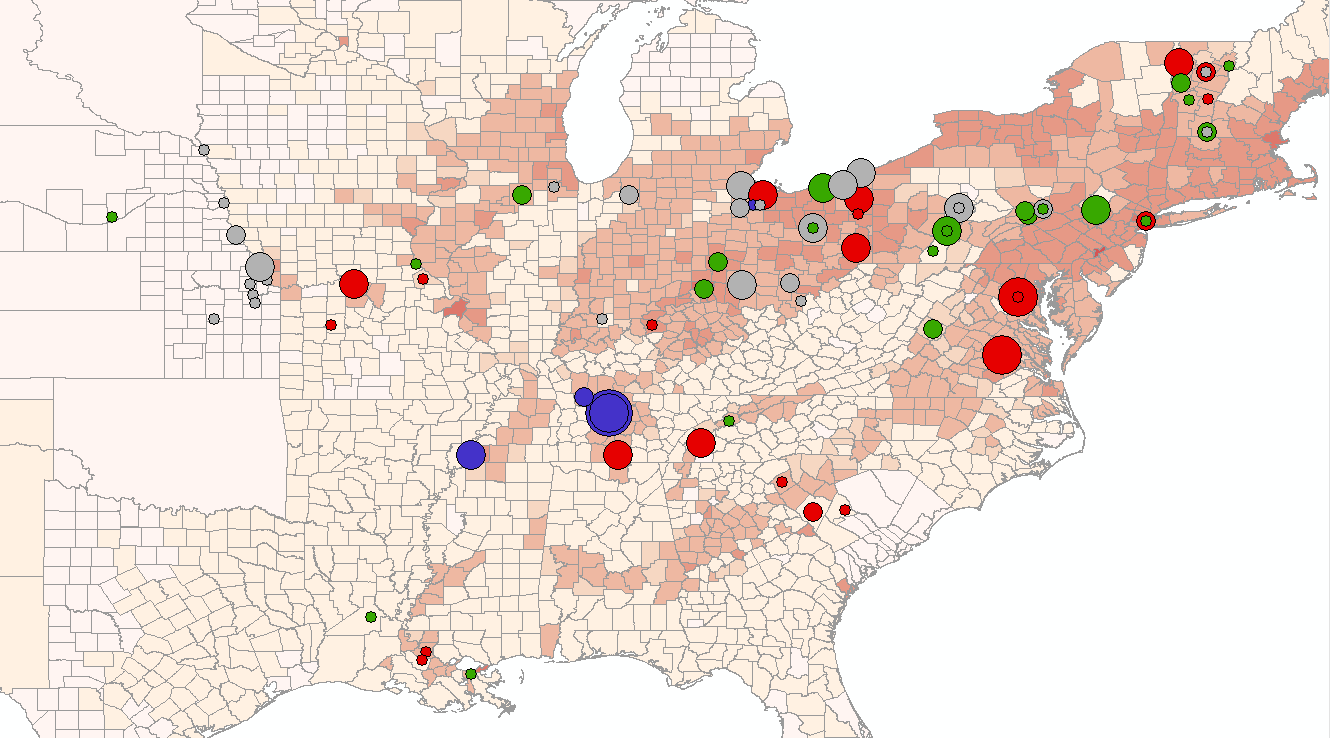

But those questions do nag at me. In particular I’ve been thinking about how we might represent the “known unknowns” of our work,1 particularly in visualizations. I really started picking at this problem after discussing the Viral Texts work with a group of librarians. I was showing them this map,

which transposes a network graph of our data onto a map which merges census data from 1840 with the Newberry Library’s Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. One of the librarians was from New Hampshire, and she told me she was initially dismayed that there were no influential newspapers from New Hampshire, until she realized that our data doesn’t include any newspapers from New Hampshire, because that state has not yet contributed to Chronicling America. She suggested our maps would be vastly improved if we somehow indicated such gaps visually, rather than simply talking about them.

In the weeks since then, I’ve been experimenting with how to visualize those absences without overwhelming a map with symbology. The simplest solution, as almost always, appears to be the best.

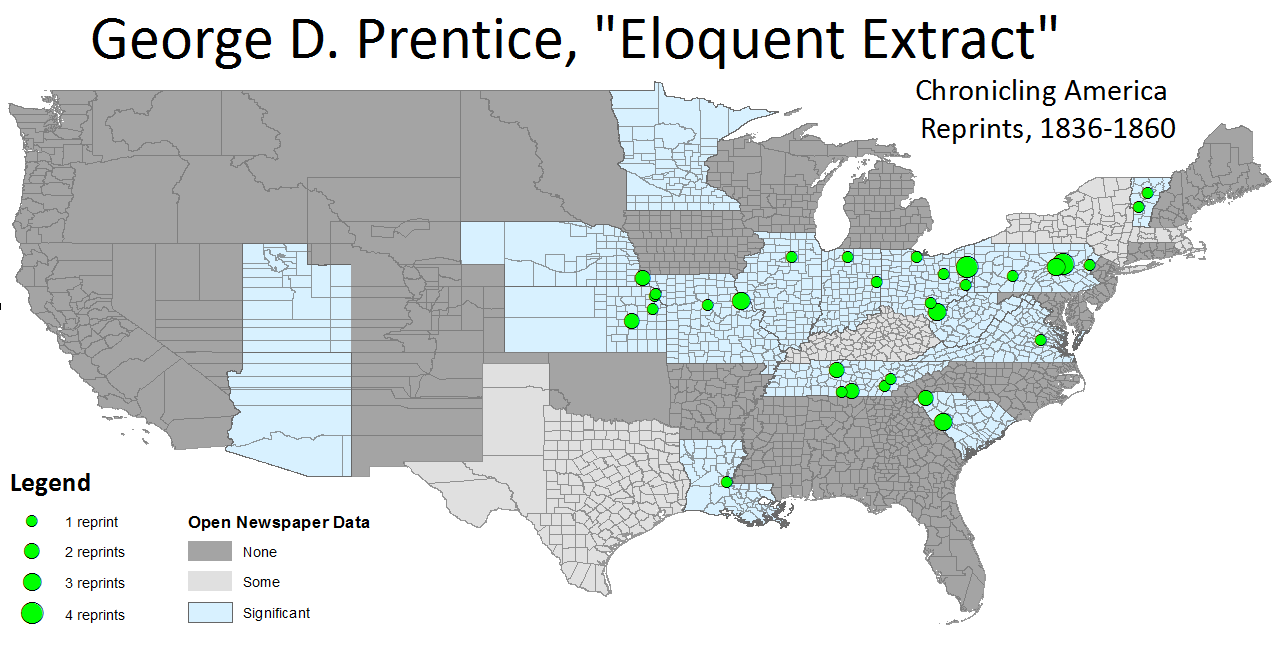

In this map I’ve visualized the 50 reprintings we have identified of one text, a religious reflection by Nashville editor George D. Prentice, often titled “Eloquent Extract,” between the years 1836-1860. The county boundaries are historical, drawn from the Newberry Atlas, but I’ve overlain modern state boundaries with shading to indicate whether we have significant, scant, or no open-access historical newspaper data from those states. This is still a blunt instrument. Entire states are shaded, even when our coverage is geographically concentrated. For New York, for instance, we have data from a few NYC newspapers and magazines, but nothing yet from the north or west of the state.

Nevertheless, I’m happy with these maps as helping me begin to think through how I can represent the absences of the digital archives from which our project draws. And indeed, I’ve begun thinking about how such maps might help us agitate—in admittedly small ways—for increased digitization and data-level access for humanities projects.

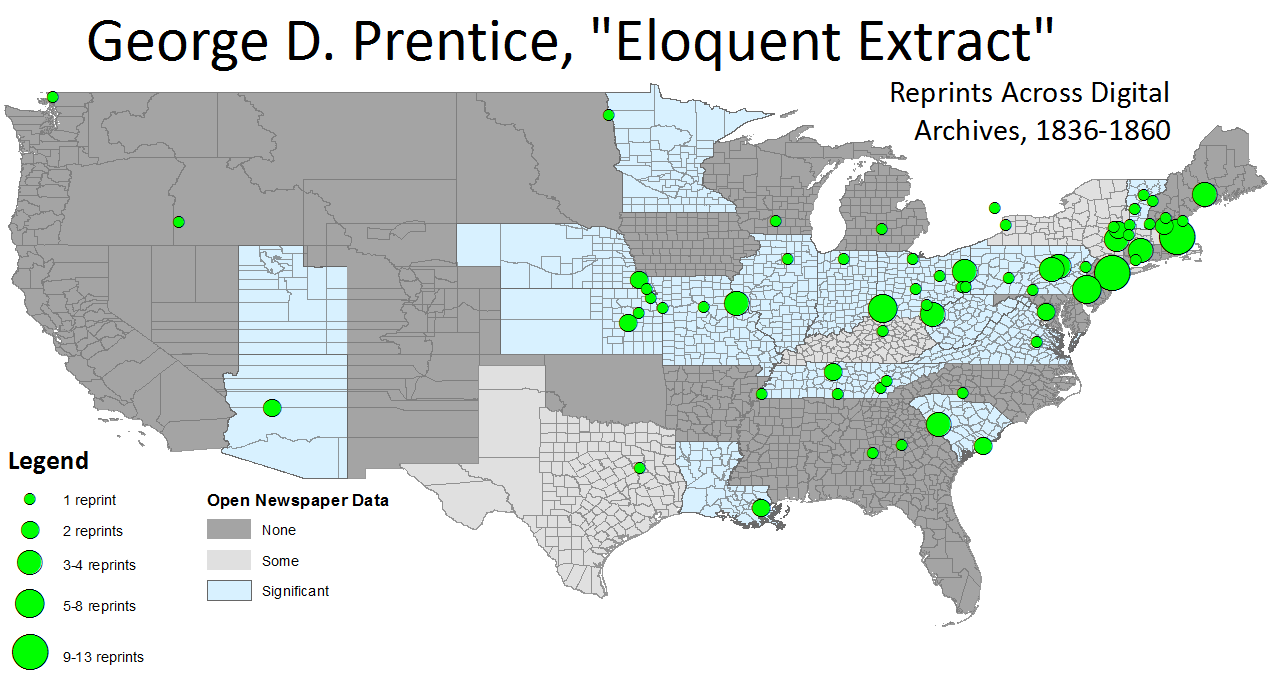

This map, for instance, visualizes the 130 reprints of that same “Eloquent Extract” which we were able to identify searching across Chronicling America and a range of commercial periodicals archives (and huge thanks to project RA Peter Roby for keyword searching many archives in search of such examples). For me this map is both exciting and dispiriting, pointing to what could be possible for large-scale text mining projects while simultaneously emphasizing just how much we are missing when forced to work only with openly-available data. If we had access to a larger digitized cultural record we could do so much more. A part of me hopes that if scholars, librarians, and others see such maps they will advocate for increased access to historical materials in open collections. As I said in my talk at the recent C19 conference:

While the dream of archival completeness will always and forever elude us—and please do not mistake the digital for “the complete,” which it never has been and never will be—this map is to my mind nonetheless sad. Whether you consider yourself a “digital humanist” or not, and whether you ever plan to leverage the computational potential of historical databases, I would argue that the contours and content of our online archive should be important to you. Scholars self-consciously working in “digital humanities” and also those working in literature, history, and related fields should make themselves heard in conversations about what will become our digital, scholarly commons. The worst possible thing today would be for us to believe this problem is solved or beyond our influence.

In the meantime, though, we’re starting conversations with commercial archive providers to see if they would be willing to let us use their raw text data. I hope maps like this can help us demonstrate the value of such access, but we shall see how those conversations unfold.

I will continue thinking about how to better represent absence as the geospatial aspects of our project develop in the coming months. Indeed, the same questions arise in our network visualizations. Working with historical data means that we have far more missing nodes than many network scientists working, for instance, with modern social media data. Finding a way to represent missingness—the “known unknowns” of our work—seems like an essential humanities contribution to geospatial and network methodologies.

1. Yes, I’m borrowing a term from Donald Rumsfeld here, which seems like a useful term for thinking about archival gaps, while perhaps not such a useful term for thinking about starting a war. We can blame this on me watching an interview with Errol Morris about The Unknown Known on The Daily Show last night.↩