Tips for Classroom Discord

Why Use Discord in the Classroom?

Before the fall semester I asked teachers on Twitter to tell me about their experiences with Discord in the classroom. My goals for Discord were simple: I wanted a less formal, community-oriented space where my students could chat with me and each other, ask questions, share fun discoveries, and generally do some of essential, social work that typically happens in the classroom. I was not looking to hold class meetings on Discord, though I know some teachers have done so successfully, but to supplement those interactions in an asynchronous way. This term I’m teaching asynchronously, so that goal has become even more important.

The replies to my initial post were valuable and also prompted some great discussion about the virtues and shortcomings of a number of social platforms, including Discord, Slack, and Element HQ, for encouraging student conversation and engagement. Folks also pointed my attention to a similar discussion on the Digital Humanities Slack (🎶 isn’t it ironic? 🎶) that I found valuable. Ultimately I decided to give Discord a try, not from any ideological commitment to it (I wasn’t even a Discord user prior to asking that question), but simply because:

- Discord seemed a bit more barebones than Slack, in a good way, in that it’s not trying to serve too many purposes beyond community and discussion;

- I loved the ease of set-up and quality of the audio channels, in particular, for student meetings and office hours;

- As I learned about roles and channel visibility—with the help of Kate Ozment—I began to understand how a single Discord server could serve all my students, both those in my classes but also the grad students I work with and students who need to communicate with me in my administrative role(s).

I should say that I did not choose Discord because I think all my students are already using it (some are; some aren’t) or out of some sense they would like it more (some do; some don’t). There’s nothing we’re doing in Discord we could not do in Slack or a similar platform, I just slightly preferred the interface and performance of Discord in a few key areas.

One unexpected outcome of my move to Discord was that it did dramatically increase student participation in my office hours (which I call student hours, an idea I learned from colleagues and could discuss elsewhere). Not only did I chat with more students in my Discord office hours than I had in my Zoom office hours in earlier pandemic semesters, I chatted with more student in my Discord office hours than I have in office hours of any semester in recent memory. Partly I think this was because of the low stakes of the audio channel compared with video or, frankly, with showing up in person at a professor’s office. Once students figured out that the Student-Hours channel was essentially an open phone line, they would pop in with just a quick question here, just a cool thing they saw yesterday there. There were the same number of sustained, long-form conversations as in a typical semester, but there were far, far more quick engagements that (I hope) helped students see me as available and proxied some of the interactions we’d typically have just before or just after class in a normal term.

For that reason alone, I counted my first experiment with Discord a resounding success and committed to using it again this spring. In the remainder of this post I want to share a few practical tips from these early forays into teaching with Discord.

Discord Tips

There are already many great tutorials—both in text and video—about setting up Discord for the classroom, including from Discord itself, so I won’t try to cover the whole process here. Instead, I want to share a few key details of setup that have been important for me, some of which I’ve learned the hard way, by doing the wrong thing initially and correcting from there. I hope folks might find these tips valuable and I’m happy to answer followup questions this post might prompt.

1. Use Roles & Categories

When first considering Discord, I was unsure whether I would have to create a separate server for each class I was teaching, as well as another for the grad students I work with. I wanted to ensure students’ privacy so that their posts were only available to their own class or group. At the same time, I did not relish having to switch constantly between servers myself. Also, I hoped to use Discord for office hours, which are typically shared among the different classes, project teams, and graduate students with whom I work. I did not want to have to schedule multiple, targeted office hours for different groups/Discord servers.

Fortunately, Kate Ozment clued me into Discord’s roles and permissions settings, which allow you to assign roles to particular users that will determine precisely which channels they can see or interact with. One user can be assigned multiple roles, too, so when I was teaching a grad course last semester a student could have both the role f20idh (i.e. a student in my graduate Introduction to Digital Humanities seminar) and the role grad-students (i.e. a grad student in my department who might have a question for me as the current Graduate Program Director). You can control roles’ access to particular channels, either on a channel-by-channel basis, or through channel categories, which allow you to set permissions for all channels under a particular category.

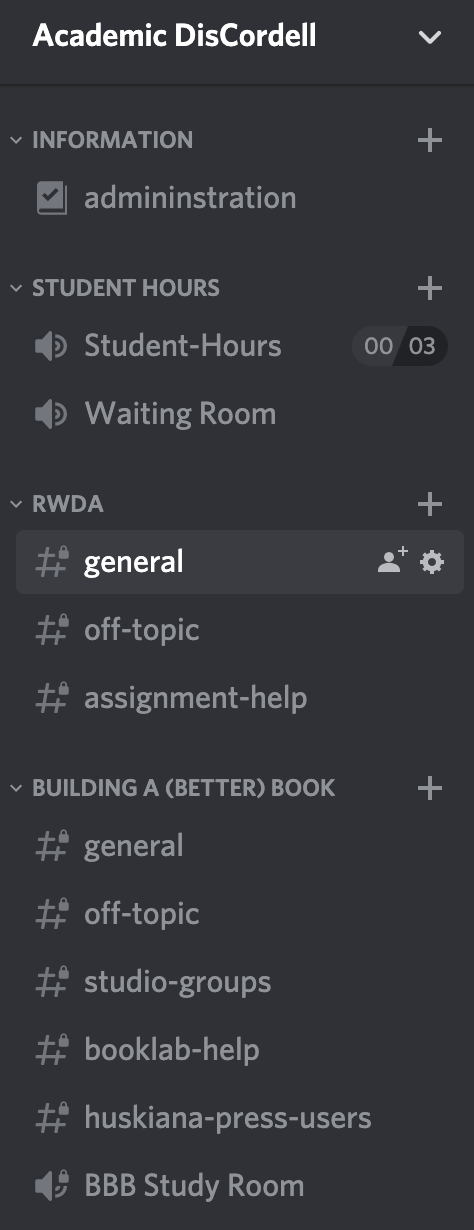

For my classes, then, I set up a single server named Academic DisCordell (it’s not even a good pun but I still love it). On that server I have a category for Student Hours, open to all roles, which houses the Student-Hours and Waiting Room audio channels, which I use for meeting with students from across my classes, projects, or administrative duties. Anyone on my server can access these channels. There’s also an Information category that houses a general administration channel. This is where users go when they first follow an invitation link to the server, and it houses the server’s code of conduct (more on that later). If you’d like to pop onto my server temporarily to see what that looks like, here’s a link.

The two categories on my server available to all users,

The two categories on my server available to all users, Information and Student Hours, and two course categories limited to students with course-specific roles assigned.

Beyond these two categories, however, I set up categories for each of my classes/groups that include the channels for those classes/groups and restrict access to users with specific roles assigned to them. That way students can interact with relevant colleagues but will not see the channels designed for students from other classes, projects, or groups.

2. Consider a Community Server

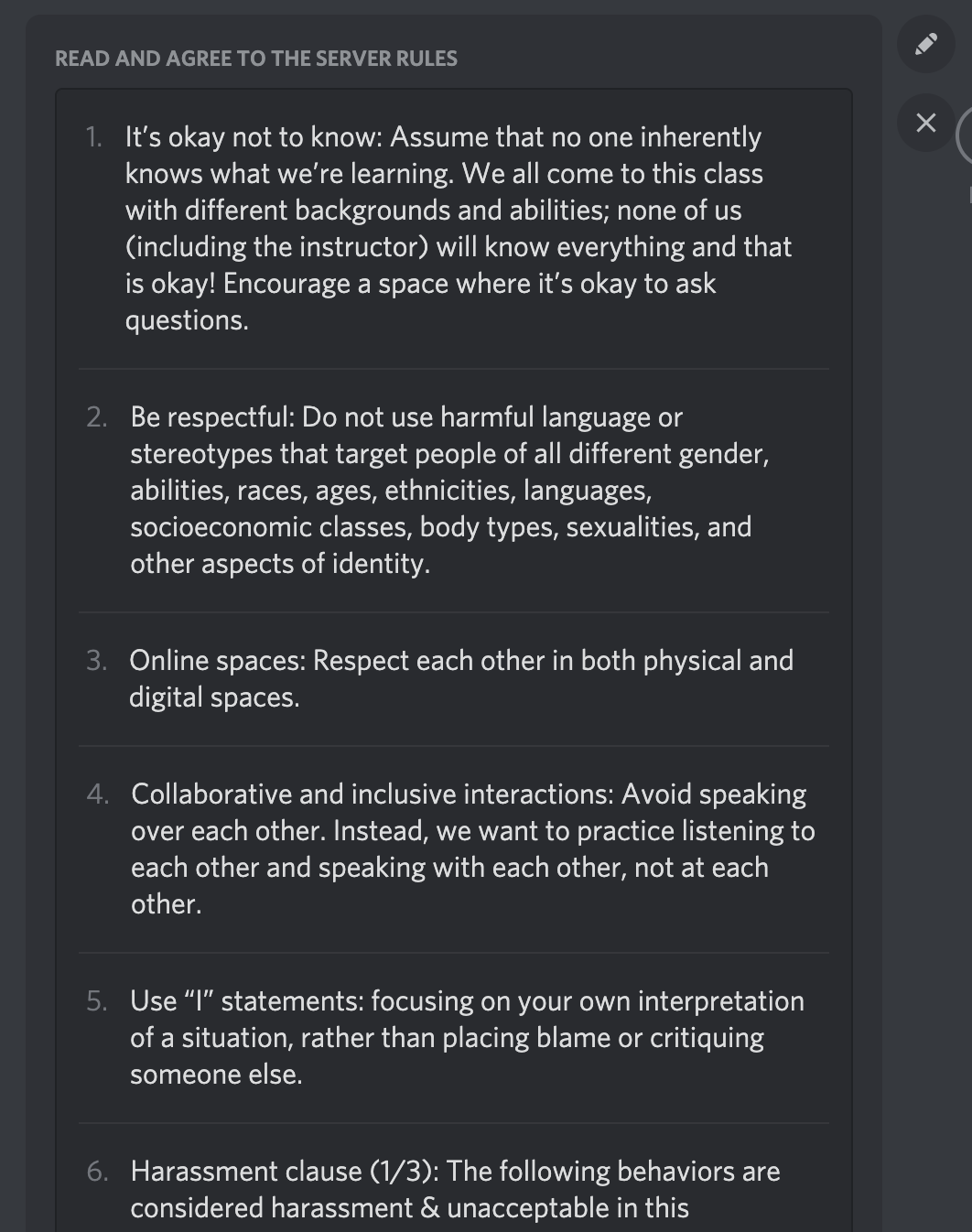

Discord allows many kinds of servers, but for mine, particularly as it serves a few different groups, it made sense to enable it as a community server. Functionally, that doesn’t change all that much, but community servers require certain features that seemed like best practice for classroom use, including higher levels of verification for users and including a channel that specifically outlines the rules or guidelines for server participation. I use a code of conduct in my classes, adapted from the sterling model provided by Northeastern’s Feminist Coding Collective, and I adapted this for my community Discord server.

Just last month, Discord announced a new feature for community servers, rules screening, which allows the server admin to present new users with a set of rules they must explicitly agree to in order to participate on the server. I adapted the code of conduct I mention above for this new feature, so now students must agree to abide by these rules when they first join the server.

The Code of Conduct for my server adapted for rule screening, so that student must explicitly agree to abide by the rules when they join the server

The Code of Conduct for my server adapted for rule screening, so that student must explicitly agree to abide by the rules when they join the server

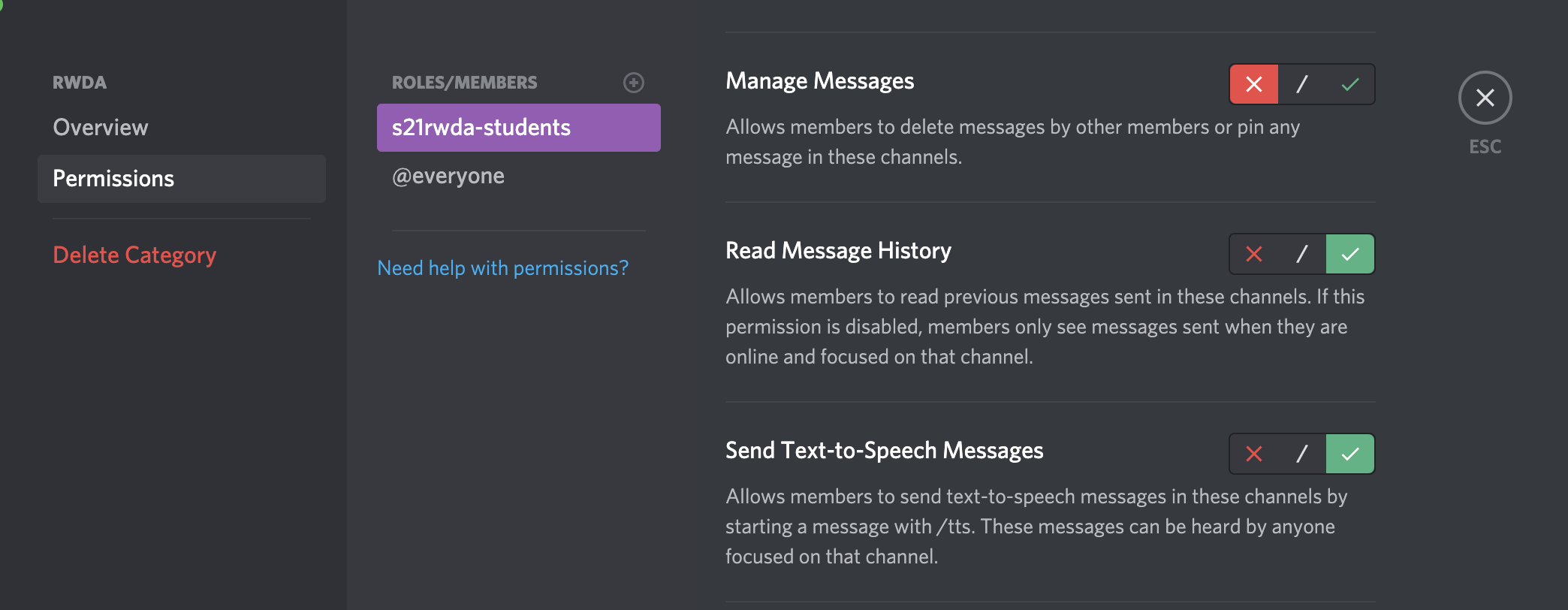

3. Make Sure “Read Message History” Is Enabled

This is a small detail, but proved important. Among the many permissions Discord allows you to set for channels or categories, “Read Message History” determines whether or not members can see all the activity in a channel, including posts from before they joined or when they were offline. If this is not enabled, the channel is a kind of “real time” discussion space, but users can only see things posted while they are online and in the channel. This is likely useful for some channels on really large servers, who want to have an active chat without users getting bogged down by a huge backlog of text, but it’s very un-useful for a channel you want students to be able to use asynchronously and reference as a resource.

For classroom servers it’s really important for ‘Read Message History’ to be enabled or students will not see most of their colleagues’ posts (or yours)!

For classroom servers it’s really important for ‘Read Message History’ to be enabled or students will not see most of their colleagues’ posts (or yours)!

I learned this one the hard way. Students were joining my server but kept messaging me saying they couldn’t see posts from their colleagues or from me, or that they couldn’t even see their own earlier posts. They were posting the same thing multiple times, which I could see—I could see all the posts and couldn’t figure out for awhile what was happening to the students. It turned out that “Read Message History” was disabled for the whole course category, and thus for all the channels contained in it! I’m not sure why this privilege had been set up this way, as I don’t remember choosing the option, but it was making the server very confusing for students to navigate and use. So: make sure your class channels enable “Read Message History,” at least for the members with the proper role for those channels.

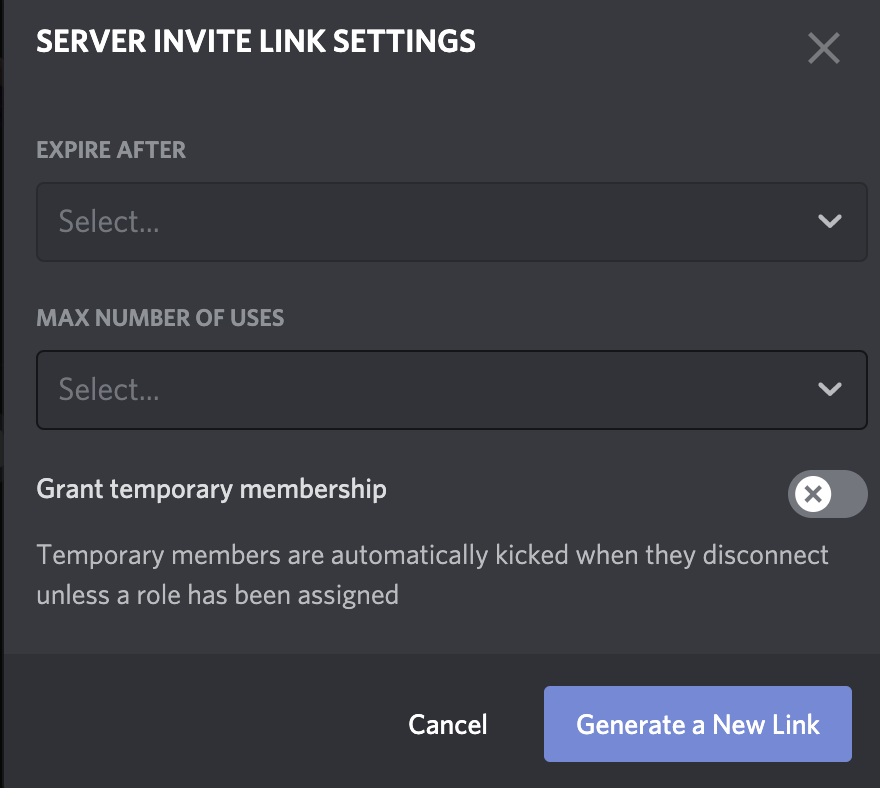

4. Do Not Use Channel Invites that “Grant Temporary Membership”

This is another lesson learned through mistake, in this case born of just not reading closely enough—a cardinal sin for an English professor! In short, your students will likely join your Discord through an invitation link that you generate and include in a class email, announcement, or assignment in your LMS. When you create these links in Discord you set several options, including how long the link will be valid (between 30 minutes and forever), how many people can use a particular one, or whether clicking the invitation will grant someone temporary membership on the server. I did not read the fine print here, and assumed I did want to grant temporary membership to students, which I thought would give me time to then make them permanent members and assign appropriate roles.

For classroom servers you probably don’t want your invitation links to grant only temporary membership, so don’t click that option.

For classroom servers you probably don’t want your invitation links to grant only temporary membership, so don’t click that option.

However, a “temporary membership” is…well…more temporary than I imagined, and expires as soon as that user logs off the server. What this meant in practice was that sometimes a student would join while I was online, and I’d see them and assign them a permanent role—perfect! However, if a student joined while I was not online, or not paying attention, and then logged off, I would be unable to assign them a role because they would no longer be a member. It’s a small detail that led to some confusion and frustration. So: when generating your invitation links for your students, make sure not to check this box so they remain members of the server long enough for you to assign their roles.

5. Make Sure Students Understand Server Rules

Some of the security features in Discord allow you to specify things like how long a user must belong to the server before they are allowed to post, what kinds of content can be posted based on role or membership duration, or whether users can do things like mute or kick off other users. These features are designed to encourage community and prevent spam or abuse, so that, for instance, a spammer can’t follow your invite link, post a litany of abuse immediately, and then log off. So I would recommend setting some of these precautions, but make sure you communicate them to students so they understand that they may have to wait a particular span of time between joining the server and participating on it.

6. Assign Training and Initial Posts

As I wrote above, you shouldn’t assume that your students have used or understand Discord. If you’re going to use it in the classroom, don’t just throw an invitation link onto your LMS and assume they’ll figure things out from there. Write a bit about why you want them to use Discord and the kinds of exchanges you hope the platform will support, and link to resources that will help students learn to use it.

I also found that however much you might want and expect students to just start chatting, sharing memes, and asking questions, just like in class discussions it’s nerve wracking to be the first. Consider requiring students to contribute an initial few posts to get the conversation started. Here’s what I asked student in my asynchronous fall classes to do:

- Sign-up for the Discord server (Links to an external site.)

- Send me a message on Discord telling me your username so I can assign you the right role and you can see our class channels.

- Once you’ve been assigned, introduce yourself in the

#generalchannel. Include your: name, major, year, pronouns, and one interesting fact about yourself. - Then, post your favorite (course appropriate) meme in the

#off-topicchannel. - Finally, post one question you have about the course structure, policies, or assignments in the

#assignment-helpchannel.

As students posted these, they also started reacting to their colleagues’ posts: sometimes with text replies, but just as often with emoji or other affirmations. I can’t say for sure that this will lead to a robust community this term—we only started two days ago—but it’s a good start.